Courtesy of Alan Jacobs’ “Confession and Autobiography” class, in which I’d love to lurk.

Courtesy of Alan Jacobs’ “Confession and Autobiography” class, in which I’d love to lurk.

Peter Thiel on startup culture:

There’s a pessimistic read on the startup culture where you could say that people, it’s not really a typical thing to start something new. That, the large institutions should have far more resources, longer time horizons and so you only need to start something new when none of the existing institutions work. Maybe the fact there’s so much stress on starting new things is the positive tip of the iceberg but the much larger, negative part of the iceberg is that the large, existing institutions are incredibly broken.

To me, this attitude (which Thiel doesn’t necessarily hold) speaks of the belief that tomorrow will be better, must be better. (I wrote about this a few months ago.) Part of what’s going on in this kind of thinking is a denial of history. You have to contort yourself into some really wild intellectual knots to believe that the past was just a bulldozer of scientific, social, and political progress. Rather than face facts, people invent new things.

Josh Gibbs says something similar in his book How to be Unlucky:

The modern man wants every ancient proverb qualified with words like “usually,” “typically,” “generally,” “often,” and “sometimes.” He does not believe there is a way things are. He does not even believe there is a way things tend to be. Rather, he views the world as a series of accidents and arbitrary events. Every thing and every person in the world is atomized, isolated in its being, sequestered off from the habits of existence. Reality has no contours; being has no grooves. The modern man does not believe women are a certain way. He does not believe men are a certain way. He does believe children or kings, farmers or prostitutes are a certain way. He believes that every human being alive is at war with the past, at war with tradition, and thus the modern man believes every farmer is reinventing farming, every kind reinventing dominion, every woman reinventing femininity. Because every farmer is reinventing farming and every woman is reinventing femininity, the terms “woman” and “farmer” are empty. We should not expect the zeitgeist to be content until every weighty word in the dictionary has been gutted. (p. 91)

On David K’s recommendation, I’m reading Jeff Goins’ book Real Artists Don’t Starve. Goins is attacking some common myths that hang around artistic types, like the idea that making money means you sold out, or the notion that success is all a matter of blind luck. Believe it or not, you can work things to your advantage in your pursuit of art. Goins distills his advice into a dozen principles, which he doesn’t call The Twelve Rules of Goins, but I’m going to.

Behold, the Twelve Rules of Goins.

1. The Starving Artist believes you must be born an artist. The Thriving Artist knows you must become one.

2. The Starving Artist strives to be original. The Thriving Artist steals from his influences.

3. The Starving Artist believes he has enough talent. The Thriving Artist apprentices under a master.

4. The Starving Artist is stubborn about everything. The Thriving Artist is stubborn about the right things.

5. The Starving Artist waits to be noticed. The Thriving Artist cultivates patrons.

6. The Starving Artist believes he can be creative anywhere. The Thriving Artist goes where creative work is already happening.

7. The Starving Artist always works alone. The Thriving Artist collaborates with others.

8. The Starving Artist does his work in private. The Thriving Artist practices in public.

9. The Starving Artist works for free. The Thriving Artist always works for something.

10. The Starving Artist sells out too soon. The Thriving Artist owns his work.

11. The Starving Artist masters one craft. The Thriving Artist masters many.

12. The Starving Artist despises the need for money. The Thriving Artist makes money to make art.

Some solid advice there. Take a closer look at #6: The Thriving Artist goes where creative work is already happening. In that chapter, Goins quotes a little detail from Patti Smith on why so many creative types moved to New York in the 1970s: “It was cheap to live here, really cheap.” Obviously NYC is the furthest thing from cheap nowadays. But the art scene of the 1970s is a big reason why the city still holds a flavor that so many hip youngsters find irresistible. Apparently the cycle goes something like this: a bunch of creative people move to a cheap town, meet each other, do their creative thing, and attract lots of other people who want to live in a happenin’ place.

That right there is seventy percent of the reason T and I moved to Birmingham. It’s cheap to live here, really cheap. When don’t have to worry so much about stacking the wampum, you have the luxury to spend your time on other, more creative pursuits. And when those creative pursuits do start to turn a profit, the profit doesn’t have to be enormous for you to make ends meet.

One final thought: my friend Daniel pointed out that there’s this assumption underneath these twelve principles that Thriving Artists are the real artists, whereas Starving Artists are poseurs. Goins makes that assumption explicit in the title of the book: real artists don’t starve. The implication is that, if you aren’t making money on your art, you’re not a real artist. When you get right down to it, is that any more helpful that the reverse? There’s nothing wrong with an electrician who writes music in his spare time and never makes a nickel from it.

Errol Morris’s 8 principles of photography:

- All photographs are posed.

- The intentions of the photographer are not recorded in a photographic image. (You can imagine what they are, but it’s pure speculation.)

- Photographs are neither true nor false. (They have no truth-value.)

- False beliefs adhere to photographs like flies to flypaper.

- There is a causal connection between a photograph and what it is a photograph of. (Even photoshopped images.)

- Uncovering the relationship between a photograph and reality is no easy matter.

- Most people don’t care about this and prefer to speculate about what they beleive about a photograph.

- The more famous a photograph is, the more likely it is that people will claim it has been posed or faked.

via Austin Kleon, whose blog is mucho worthwhile

Dinner tonight at Highlands Bar & Grill, winner of the James Beard award.

Did you know this? I didn’t. Tolkien was always the doodler in my mind.

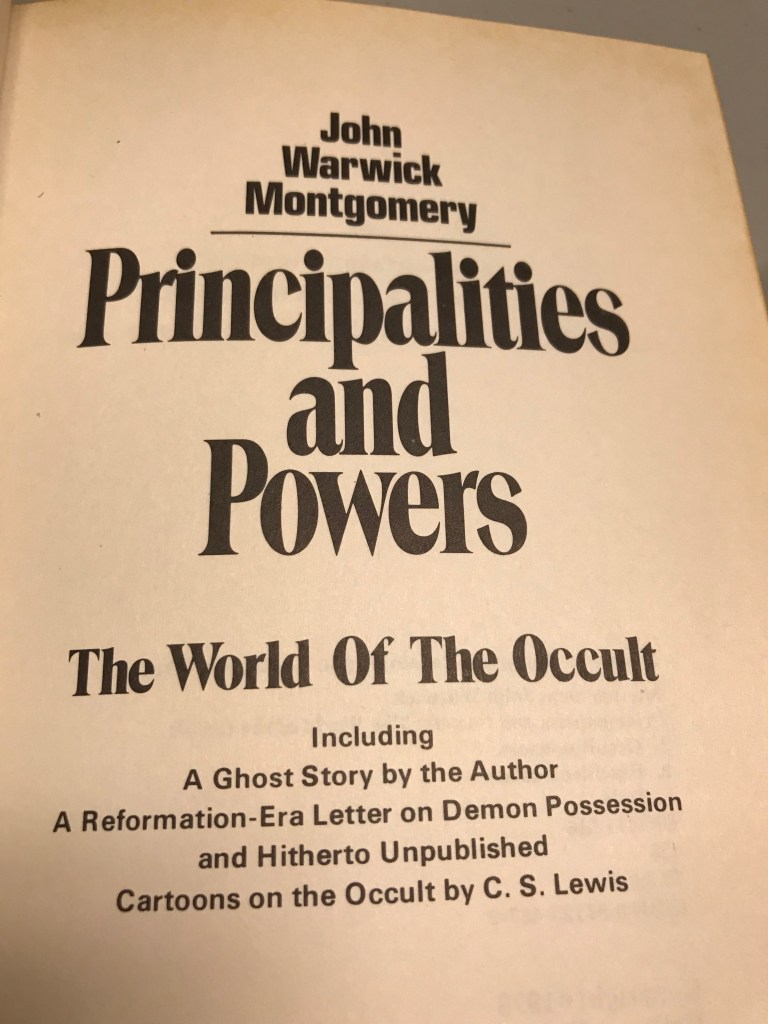

Cataloguing books at Theopolis today, I snagged my eye on the subtitle of this one.

“Hitherto Unpublished Cartoons on the Occult by C. S. Lewis?”

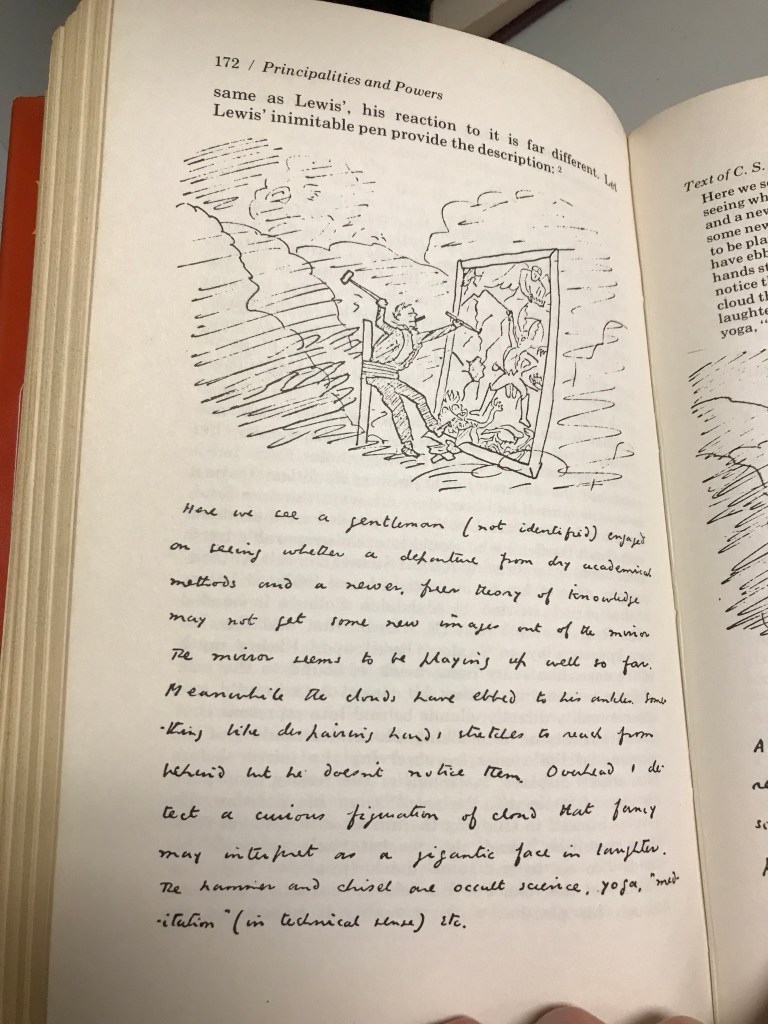

I flipped through till I found them.

The context is a letter from Lewis to his friend Owen Barfield, who was toying with occultist ideas like anthroposophy (which I have known about for around ten minutes). Lewis is explaining to Barfield why his approach to reality is flawed – the letter is headed “The Real Issue between Us.” I’ll let the author summarize the rest. (It’s worth noting that Lewis wrote this before becoming a Christian.)

Lewis first describes his own approach by an analogy based upon Plato’s myth of the cave: like every man, Lewis is bound to the post of finite personality so that he cannot turn around and observe reality directly; clouds behind him represent that ultimate reality or True Being. His understanding of the meaning of life comes by observing the mirror before him, which displays “as much of the reality (and such disguise of it) as can be seen” from his position. He devotes himself to studying the mirror with his eyes (“explicit cognition”) and also reaches backward with his hands “so as to get some touch (implicit “taste” or “faith”) of the real.” For Barfield the occultist, however, though his position vis-à-vis reality is necessarily the same as Lewis’, his reaction to it is far different.

What I take away from Lewis’s little attempt at art, besides once again recognizing the man’s incredible gift for coming up with analogies, is his attitude toward his own drawing. In his description of the first sketch, he seems to barely recognize the details of what he drew, almost as though he’s discovering it for the first time: “something like despairing hands,” “I detect a curious figuration,” “fancy may interpret.” I wonder if this is something that undergirds Lewis’s imagination throughout his career as a writer, that sense of exploring his own creations as though they carried on a lively existence completely independent of their maker.

Jon T. introduced me to Chris Staples’ stuff. They had him out to the Modest Music Fest in Moscow and apparently, in addition to being a great musician, he’s a total ham.

I know almost nothing about what makes music great. Of all the forms of entertainment in my life – fiction, poetry, movies, TV – music is the one about which I am most likely to say, “I just like it. I don’t know why.” But I’ll try to give a little defense of Chris Staples.

His music is often quiet, which could make you think that it’s simple. But it’s not. There’s a lot going on under the surface, a lot of different layers to listen to. My favorite songs of his have a syncopated rhythm that makes them almost seem to have two “speeds,” if that’s the right word. Listen to “Golden Age,” “Black Tornado,” or “Dark Side of the Moon” to see what I’m talking about.

He has a great blurb on his Google Play profile, too, courtesy of who knows:

There are no casual Chris Staples fans. The man inspires devotion. The turnaround from casual listener to evangelist is nearly instantaneous. Play his music during a road trip with friends and inevitably someone will ask, “Who is this?” And a lifelong fan is born. Such is the unaffected power of these songs, of this voice. Chris Staples fandom is rewarding and lasting (despite his understated approach to promoting his own work, which – as it should be with all artists – seems secondary to the effort he puts into the making of it). We follow where he leads, and our numbers are growing.

I wrote this for Curator Magazine in 2016 on the occasion of Beverly Cleary’s 100th birthday. It’s still up on their site, but since they haven’t published anything for a while, I wonder how much longer it will be. I decided to reproduce the essay here just in case.

E. B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web, was once asked by an interviewer if he ever felt the need to “shift gears” when writing for children. He replied, “Anybody who shifts gears when he writes for children will wind up stripping his gears… Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time. You have to write up, not down.”

Christian virtues are not necessarily encouraged by authors—or by any artists, for that matter. But what White describes in this interview sounds a lot like the Christian virtue of charity. In its most basic sense, charity just means love. It refers to the love that God has for us, the love that we return to Him, and the love that we show to one another as a result of our relationship with God.

At another level, charity can mean creating space for one another, giving up one’s own life and easy happiness for the sake of someone else. It is making room for others. In that sense, White’s advice boils down to writing with charity. He reminds would-be authors that, if they want to write stories for children, they need to humble themselves and be willing to lay aside their own agenda. You have to be willing to “write up.”

One of the best models of this kind of charitable stance is Newbery Award-winning children’s author Beverly Cleary, who created some of the most well-loved characters in children’s literature. Today–April 12, 2016–is Cleary’s one hundredth birthday, and yet she remains stubbornly unimpressed with herself. When an interviewer asked her a few weeks ago if she was excited to turn 100, Cleary answered, “Well, I didn’t do it on purpose.”

The naturalness of getting older is a common theme in Cleary’s books, as is her commitment to the mundane sorts of experiences that make up life. Cleary’s books, for the most part, are written from the point of view of young children, and always remain true to the complexities and confusions of growing up. The problems of Henry Huggins, Otis Spofford, Ellen Tebbits, and Ramona Quimby are real problems, and Cleary takes them seriously. Rather than insert her adult perspective into the pages, she bows to her characters’ wishes, taking care to explain their motivations, which make perfect sense to them, of course.

In other words, Cleary’s books show her willingness to make room for her characters to take on lives of their own. As a result, her characters are imminently relatable, even lovable, especially the spunky, imaginative Ramona Quimby. Few characters in children’s literature have as rich as inner life as Ramona, and fewer are given room to explore it.

Ramona lives in Portland, Oregon, on Klickitat Street—a real street where Cleary lived as a girl. Ramona’s father works at various blue collar jobs and her mother sometimes picks up work at a doctor’s office. There is also Ramona’s older sister, Beatrice (called “Beezus”), who tolerates her, and Picky-picky, the cat, who despises her.

Cleary was once asked why so many people relate to Ramona, who is by far Cleary’s most popular character. She said, “Because she does not learn how to be a better girl.” Cleary was annoyed with the books she read in her childhood because the characters always learned how to “be better children.” In her experience, children did not learn how to be better children. They just grew up.

That’s not to say Ramona doesn’t learn things. Some of her most memorable experiences involve an unpleasant or confusing realization about herself. For example, at the beginning of Ramona the Brave (not the first book in the Ramona series, but the first that I was introduced to), Ramona is trotting home behind her big sister, mightily pleased with herself. She has just told off a group of boys who were making fun of Beezus’s nickname, which incidentally, Ramona gave her. It’s not until the girls get home that Ramona discovers that her “sermon,” as Beezus puts it, was not at all appreciated by her sister. Beezus was as embarrassed that Ramona came to her defense as she was by the teasing in the first place. Poor Ramona had no idea that she could hurt her sister’s feelings by standing up for her.

“Ramona was used to being considered a little pest, and she knew she sometimes was a pest, but this was something different. She felt as if she were standing aside looking at herself. She saw a stranger, a funny little six-year-old girl with straight brown hair, wearing grubby shorts and an old T-shirt, inherited from Beezus, which had Camp Namanu printed across the front. A silly little girl embarrassing her sister so much that Beezus was ashamed of her. And she had been proud of herself because she thought she was being brave. Now it turned out that she was not brave. She was silly and embarrassing. Ramona’s confidence in herself was badly shaken.

This kind of inside-outside comparison between Ramona’s imagination and her reality continues throughout the Ramona stories. Ramona rarely finds her expectations met when it comes to the reactions of others. Something that she takes great pride in might be ignored by everyone else, or worse, mocked. Something that Ramona takes as logical fact turns out to be a source of embarrassment for her, like when she sits quietly for a long time waiting for her teacher to bring her a gift, all because the teacher told Ramona to “sit here for the present.”

Roger Sutton, writing for the New York Times, commented that Cleary’s novels put kids on a level playing field with adults. Ramona doesn’t understand everything that happens around her, but she makes note of the glances that pass between her parents and the way Beezus acts when she gets a bad haircut. Ramona is often embarrassed, but Cleary is careful that Ramona never, ever looks dumb, either to adults in the story or to her readers. In fact, sometimes Ramona’s version of things makes more sense than the truth. Why doesn’t the word “attack” mean to stick tacks in people?

A less charitable author would take a moment like this and pat the character on the head, saying, “How cute.” Yet Cleary never uses a simpering tone or condescends to her characters. Instead, she sympathizes with them, and so do we. At one point, Beezus, in a fit of exasperation, says to Ramona, “Grow up!” Without missing a beat, Ramona yells back, “Can’t you see I’m trying?”

Ramona’s embarrassment at being herself, and especially at being herself without knowing what she was doing, could easily have been turned into a fable of some kind, where Ramona learns to be obedient, or maybe to be true to herself and be recognized for that honesty. But Cleary is too devoted to her little character (and too respectful of children) to leave Ramona with that kind of bow on her story. After all, most of us didn’t grow up through a series of character building episodes, one after the other. Childhood is messier than that.

That’s not to say that Cleary refuses to give Ramona a happy ending. Ramona the Brave ends with Ramona proud of herself once again for having stood up to a mean dog who stole her shoe. She remains self-aware, as always, but for the time being, she has recovered her bravery.

“Of course, she was brave. She had scars on her shoe to prove it… Brave Ramona, that’s what they would think, just about the bravest girl in the first grade. And they would be right. This time Ramona was sure.”

It’s hard to read one of Beverly Cleary’s stories without a glimmer of recognition at something one of the children is going through, whether it’s learning to read or finding something to do on a summer afternoon. It’s even harder to read one of her stories without seeing her self-sacrificial love for her characters covering every page. So, happy birthday, Beverly Cleary, storyteller of charity, and thanks for “writing up.”