Coming to a Mailbox Near You

This is the first of a series of posts about Dorothy Sayers’s essay “The Lost Tools of Learning.” I think that’s sufficient introduction for anyone who reads this blog.

Also, I’m going to call her Dottie throughout, because I want to.

One of the first things Dottie does in her speech is propose “to deal with the subject of teaching,” for the purpose of producing “a society of educated people, fitted to preserve their intellectual freedom amid the complex pressures of our modern society.” Like every thirty-two-year-old academic, she aimed high, at no less than an overhaul of modern education, to correct the woefully slack thinking that ran rampant through the England of her day. She helpfully lists some examples of the problem she wants to solve:

Serious problems, these. Worth addressing.

Here’s where things get sticky. Does the average graduate of a classical school fare any better than his public school peers when it comes to:

I’m sure Dottie would agree that, even in her day, exceptional students avoided these pitfalls. Her proposals weren’t meant to improve the lot of the exceptional, but of the average. We’re talking about the typical CCE student, the Classical Child-Not-Left-Behind.

If average graduates of classical Christian schools routinely make the mistakes Dottie lists above, then either a) her proposal doesn’t work or b) we haven’t implemented it correctly.

Check out this artwork by Aedan Peterson, illustrator of The Story of God With Us, for a project based on the concept, “What if Moby-Dick took place in the desert?”

Read about his process on his blog.

Jehan Georges Vibert was like a 19th century Norman Rockwell. Here’s his depiction of “The Committee on Moral Books”:

More here.

1 Apply the seat of your pants to a chair in a very quiet room.

2 Focus with undivided attention. There shouldn’t be any distractions, especially no music blasting through earphones.

3 Conceptualize, conceptualize, conceptualize. Students often say they made a design because they felt like it. They too rarely say they did it because they thought it through and wanted to use THIS concept.

4 Sketch out thumbnails with a thick black marker—a pencil or pen will make your drawings too fussy. Fussy is good when refining an idea, but you can’t refine “nothing.”

5 Ask yourself questions to help define the problem—you are your own best resource.

6 Push yourself to explore something new. There are wonderful things inside you, and if you don’t try things you’ve never done before, you will never find them. Keeping yourself off balance will help.

7 Enlarge some of your thumbnail sketches. There are times when a wonderful little fragment of a drawing is there, but you don’t know it or see it when it’s too small. Do it mechanically—on a copier or scanner. The tools are there, so use them.

8 Don’t be afraid to put stupid things down as ideas. The point is to keep moving forward—you can weed out bad ideas later.

9 Use symbols. Don’t make pictures of whatever happened—there is rarely an idea in that approach. BUT, don’t take the search for a symbol too literally by making a trademark.

10 Be your most severe critic. The only person you ought to be competing with is yourself. Push yourself in your sketch phase. Think of it as climbing a hill with a rock on your back—it seems like you are never going to get anywhere, but what you’re actually doing is investing—in the project and in yourself.

From Guide to Graphic Design, by Scott W. Santoro, Pearson Education; it came to me via Scott W. Santoro

See some of Goslin’s designs here.

This is this week’s edition of Time’s Corner, my bi-weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

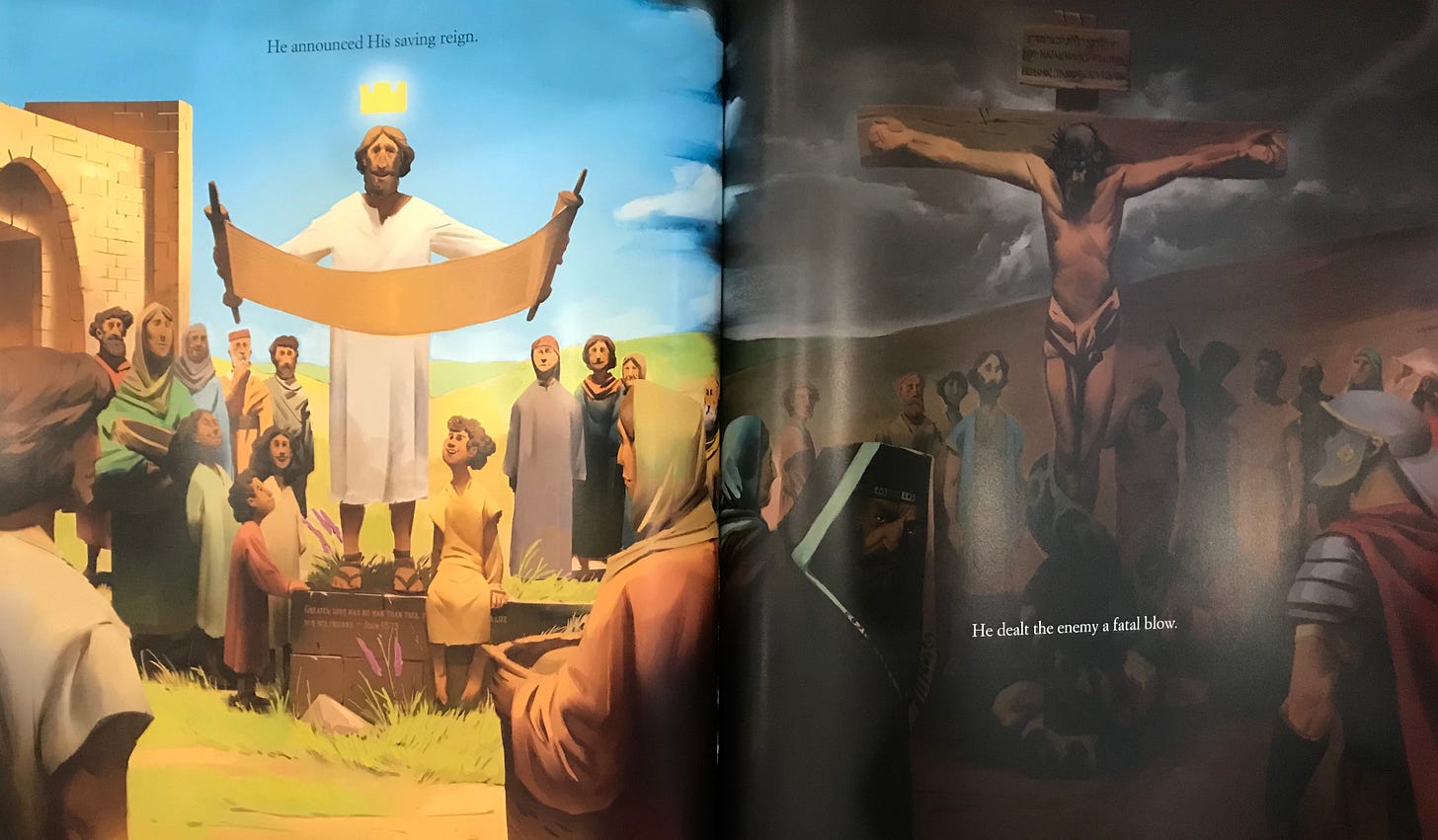

Behold! My friend Brian Moats and I have started a publishing company! It’s called Little Word. We create children’s books that teach Biblical symbols and patterns, particularly typological motifs. Read more on our website. (If you click on only one link today, make it this one.)

Years ago, I saw this posted on Twitter:

At the time, I had already toyed with the idea of creating a “Through New Eyes for Kids” book series, and when I saw this tweet, I realized a series like that would have an audience. I opened a notebook and started scribbling down ideas.

Later that same year, I happened upon Anne-Margot Ramstein’s picture book Before/After. There are no words in the book, nor any story. Instead, each page spread has two pictures side by side and you’re invited to figure out the connection between them. Despite the fact that there’s nothing to read or fiddle with, it’s one of the most interactive books I’ve ever read.

One of the most common connections between the two pictures is time—hence the name: Before/After. A beehive becomes honey. A jungle becomes a city. Sometimes, Ramstein highlights time’s cyclical nature. Day, night. Summer, winter. High tide, low tide. My favorite pages are where one object remains fixed while everything around it changes. Time acts more slowly on some things than others.

This struck me as powerful way to depict typology. Take Samson. Arms outstretched, one hand on each pillar, positioned in exactly the same way that Jesus was on the cross. Put Samson and Jesus on two facing pages and invite the reader to make connections between them. Even a child could do it—especially a child.

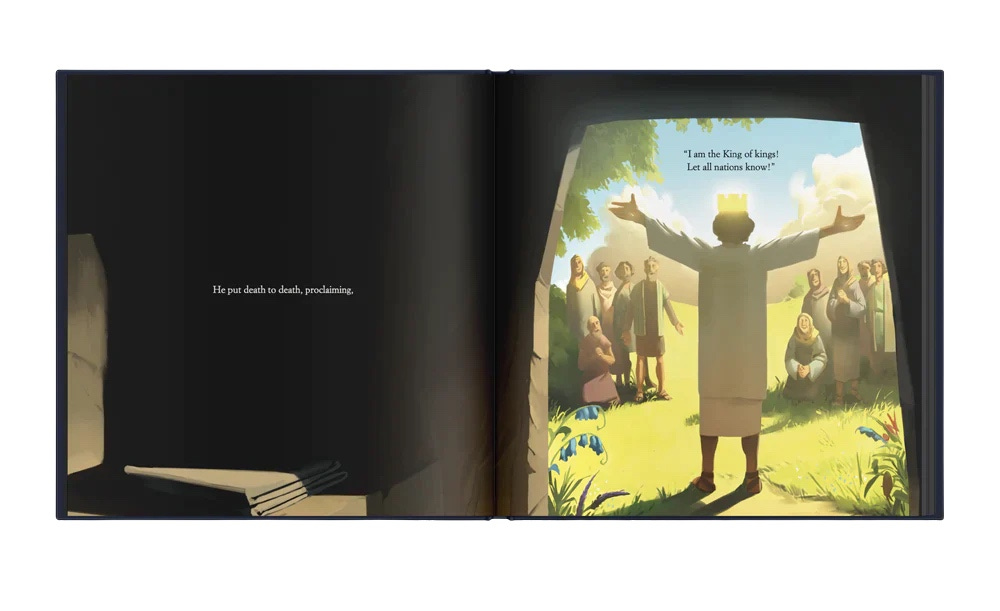

Aedan Peterson actually did something like this in Ken Padgett’s The Story of God Our King. Three sequential pages show Jesus in the same posture, arms oustretched, while the scene changes around him.

Pretty cool.

Meanwhile, in his home office, Brian had been editing hours upon hours of footage of Jim Jordan, Peter Leithart, Alastair Roberts, and Jeff Meyers talking about Biblical typology. He had taught youth Sunday school classes on Through New Eyes and The Lord’s Service and found his students extremely receptive to the ideas in those books. It was just a matter of time before Brian decided to adapt Jordan and Meyers for kids. He approached me about the idea and lo! Little Word was born.

I’ll keep you updated on our progress here at Time’s Corner, but the best way to stay informed is to follow Little Word on all the socials. Click for the ‘gram, the Tweetster, the Facity-Face, etc.

And my great wish is, that young people who read this record of our lives and adventures should learn from it how admirably suited is the peaceful, industrious, and pious life of a cheerful, united family, to the formation of strong, pure, and manly character.

Johann David Wyss, The Swiss Family Robinson

Imagine, instead of asking someone “Where do you go to church?” or “Where do you worship?”, you asked, “Where do you go every week to renew your covenant with God?”

It throws a different light on your choice of church, that’s for sure.

Once upon a time, the word “technology” might have been applied to something such as a new design element that reduces frictional losses in a gear set. Today, the word is often shortened to “tech” and it typically means: finding new ways to insert a layer of fussiness into some aspect of life that is not yet subject to

Matthew Crawfordfussiness“optimization”, and then collecting rents from the friction this introduces.