Medea

The death of blogs has been greatly exaggerated, or more likely falsely assumed. Geoff Manaugh’s blog is always worth reading, and since he’s been posting more regularly, I was able to read several good posts in a row.

First, I read this amazing description of his high school Latin teacher’s classroom:

To this, I’ll briefly add that I studied Latin in both Middle and High School, where our teacher actually lived in his room—a story for another day—a wood-paneled chamber lined with floor-to-ceiling book shelves and marble statues everywhere, including a stained glass window overlooking our school’s back quad. But, amongst all those books, from Catullus to Ovid and beyond, was a shelf devoted to vampirism, lycanthropy, and witchcraft—including titles by Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers (translator of the book seen here). I used to spend hours reading through that stuff—witch trials, premature burial, people cursed to wander the Earth alone for eternity.

It wasn’t till later in the post I realized that my wife taught at this school for a few months when we lived in Philadelphia.

He also wrote a fascinating description of the many layers of Berlin. My favorite part of the post, however, is the phrase “The SCUBA divers of the Potsdamer Sea.” Sounds like the title of a short story.

And then there was this post about liquid computers, which Geoff very sensibly connects to magic pools, ancient and medieval. The barrier between science and magic grows ever thinner.

Whatever, keeping its proportion and form, is designed upon a scale much greater or much less than that of our general experience, produces upon the mind an effect of phantasy.

A little perfect model of an engine or a ship does not only amuse or surprise; it rather casts over the imagination something of that veil through which the world is transfigured, and which I have called “the wing of Dalua”; the medium of appreciations beyond experience; the medium of vision, of original passion and of dreams. The principal spell of childhood returns as we bend over the astonishing details. We are giants—or there is no secure standard left in our intelligence.

So it is with the common thing built much larger than the million examples upon which we had based our petty security. It has been always in the nature of worship that heroes, or the gods made manifest, should be men, but larger than men. Not tall men or men grander, but men transcendent: men only in their form; in their dimension so much superior as to be lifted out of our world. An arch as old as Rome but not yet ruined, found on the sands of Africa, arrests the traveller in this fashion. In his modern cities he has seen greater things; but here in Africa, where men build so squat and punily, cowering under the heat upon the parched ground, so noble and so considerable a span, carved as men can carve under sober and temperate skies, catches the mind and clothes it with a sense of the strange. And of these emotions the strongest, perhaps, is that which most of those who travel to-day go seeking; the enchantment of mountains; the air by which we know them for something utterly different from high hills. Accustomed to the contour of downs and tors, or to the valleys and long slopes that introduce a range, we come to some wider horizon and see, far off, a further line of hills. To hills all the mind is attuned: a moderate ecstasy. The clouds are above the hills, lying level in the empty sky; men and their ploughs have visited, it seems, all the land about us; till, suddenly, faint but hard, a cloud less varied, a greyer portion of the infinite sky itself, is seen to be permanent above the world. Then all our grasp of the wide view breaks down. We change. The valleys and the tiny towns, the unseen mites of men, the gleams or thread of roads, are prostrate, covering a little watching space before the shrine of this dominant and towering presence.

Hilaire Belloc, Hills and the Sea

The man… who sings loudly, clearly, and well, is a man in good health. He is master of himself. He is strict and well-managed. When people hear him they say, ‘Here is a prompt, ready, and serviceable man. He is not afraid. There is no rudeness in him. He is urbane, swift, and to the point. There is method in this fellow.’ All these things may be in the man who does not sing, but singing makes them apparent.

Hilaire Belloc, Hills and the Sea

Drop by if you’re at Council.

The school asked me to write something about the Christian values reflected in our fall play, The Importance of Being Earnest. You can read it below. But first, behold this illustration of the play’s opening scene by one of the young actors.

Here’s the blurb:

Worn out by being a constant model of respectability at his country estate, young Mr. Jack Worthing occasionally pops up to London to visit his imaginary and very badly behaved brother Earnest. In London, Jack steps into the role of Earnest, entertaining himself and his ne’er-do-well friend Algernon Moncrieff. When the fun is over, Jack retires to the country, where he once more plays the part of role model.

Most of the social satire in The Importance of Being Earnest has leaked out since it was first performed in 1895, and what remains is almost pure farce. No one in the play has his head screwed on straight, and the plot is barely believable, but that is no doubt what has contributed to its ongoing popularity. It is ridiculous, yes, but life is often ridiculous. The characters are silly, but who among us has not been silly? The key is to recognize the fact. Jack Worthing tries to keep life and fun in separate boxes and consequently finds it almost impossible to laugh at himself. His constant seriousness is, as Algernon dryly remarks, a sign of “an absolutely trivial nature.” The graver Jack is, the fussier he gets over the smallest things in life.

Oscar Wilde subtitled his play “A Trivial Comedy for Serious People.” Perhaps the most important thing about The Importance of Being Earnest is its triviality. The wise man knows that not everything can be taken seriously, least of all himself, and the play reminds us of this truth.

Too much gravity flattens a man, but a little comedy will restore him to his natural shape.

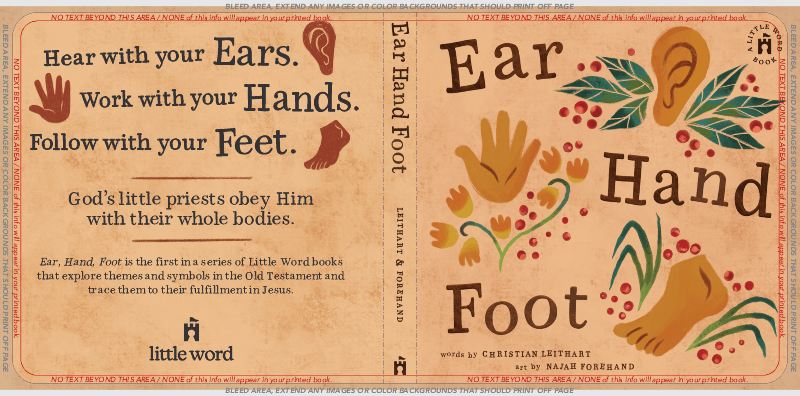

Just ordered a couple display copies of Ear, Hand, Foot for you to see at Council. It’s gonna be sweet.

Poets are so much like dancers who ruin their ankles for the sake of a moment’s beauty in the air.

Colum McCann

Alastair Roberts was good enough to mention Psalm Tap in a recent newsletter.

A poem feels finished when I can’t enter it again. Everything falls into place, each line feels balanced and complete, the shifts between lines and sentences feel shocking but also permanent and incapable of change. This poem is finished. I have to make something new. I have to be a different poet.

Richie Hofmann: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2023/06/14/making-of-a-poem-richie-hofmann/

And:

I have often found… that sometimes the best revision of a draft is the writing of a new poem.