Jacob’s story, like David’s, is virtually unique in ancient literature in its searching representation of the radical transformations a person undergoes in the slow course of time. The powerful young man who made his way across the Jordan to Mesopotamia with only his walking staff, who wrestled with stones and men and divine beings, is now an old man tottering on the brink of the grave, bearing the deep wounds of his long life.

Robert Alter

Tag Archives: Quotes

Happy at Home

To be happy at home is the ultimate result of all ambition, the end to which every enterprise and labour tends, and of which every desire prompts the prosecution.

— Dr. Samuel Johnson, The Rambler, 1750

via

UPDATE – 6/26/25

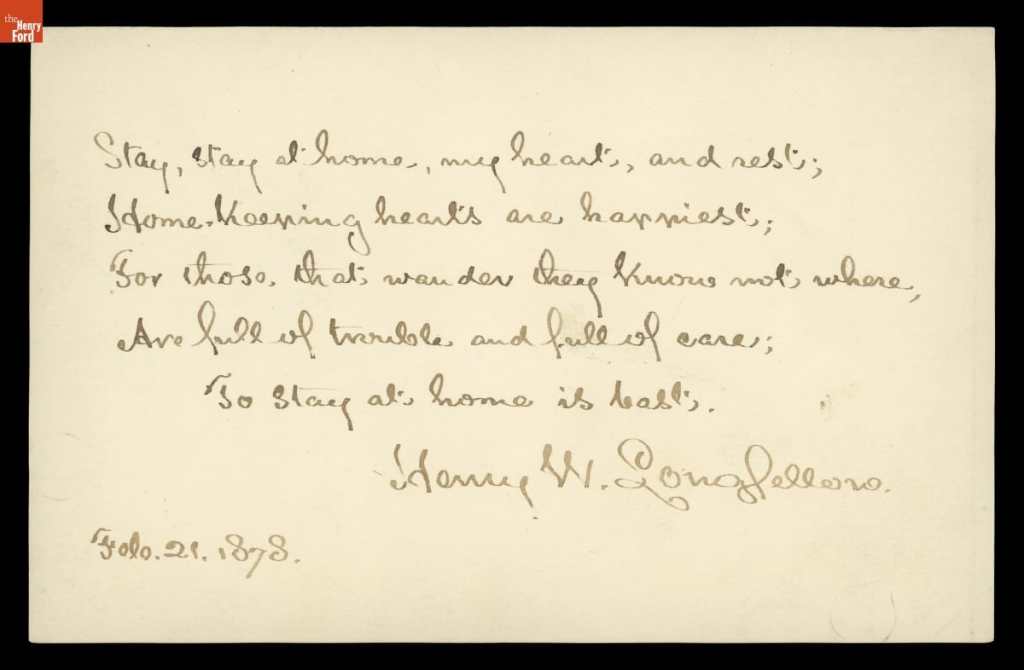

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was often visited at home by fans, many of whom wanted his autograph. He wrote a short poem and had copies made so as to have a ready supply on hand. Here’s what he wrote:

Stay, stay at home, my heart and rest.

Home-keeping hearts are happiest.

For those that wander they know not where,

Are full of trouble and full of care,

To stay at home is best.

What Copyright is For

If you ask most people what copyright is for, they’ll tell you it’s about protecting artists. But that was never its goal. It was only meant to incentivise creative work by granting a temporary monopoly to its creator. By limiting control to a set period, the system was supposed to encourage production while guaranteeing that works would eventually enter the public domain for collective use. Case in point: when the US first implemented copyright in 1790 (inspired by similar laws in Britain), protection lasted just 14 years, with a one-time renewal for another 14. Early lawmakers saw copyright as a tradeoff – short-term exclusivity in exchange for long-term public access. As a federal appeals court put it in Authors Guild v. Google Inc. (2015), “while authors are undoubtedly important intended beneficiaries of copyright, the ultimate, intended beneficiary is the public.”

Elizabeth Goodspeed

Step Aside, Marianne

Etymonline is a can-opener, an imaginary labyrinth with real minotaurs in it, my never-written novel shattered into words and arranged in alphabetical order.

Doug Harper, founder of Etymonline

Support the Finishing

Sometime I think that, even amidst all these ruptures and renovations, the biggest divide in media exists simply between those who finish things, and those who don’t. The divide exists also, therefore, between the platforms and institutions that support the finishing of things, and those that don’t.

Finishing only means: the work remains after you relent, as you must, somehow, eventually. When you step off the treadmill. When you rest.

Finishing only means: the work is whole, comprehensible, enjoyable. Its invitation is persistent; permanent. […] Posterity is not guaranteed; it’s not even likely; but with a book, an album, a video game: at least you are TRYING.

Robin Sloan

I didn’t know it at the time, but this was surely the impetus behind Good Work, a reaction against the endless “now” of social media. A print magazine must be finished before it be mailed to subscribers. When it’s finished, it’s done. It exits. The work has ended for now. You can rest.

In the new year, I plan to start a crowdfunding campaign for a limited run of Good Work. I think that’s the way forward: plan the issues, raise money, write, print, send. I’m sure I’ll cite Robin’s newsletter here in support of the project.

An Ambassador from the Transcendent World

Teacher: The modern world isn’t the only world there is, though. There is another world and it is at play right now—it’s a world behind the modern world, beneath it, beyond it—and you might need to walk around in this world “for more than ten minutes” in order to understand how things work there. [This book] is an artifact from this other world, and the way I’m interpreting it for you is a skill born of this other world. Every day during class, I do my best to present this world to you—to create entrances into it, so you can spend a little time there and see “how they do things there.” But, it’s difficult.

Student: Why?

Teacher: Because it’s not a physical place and I can’t force you to go there. It’s an intellectual place, a spiritual place, and the only way to enter this place is to genuinely want to be there—and you have to want to be there before you fully understand what it is.

Student: I’ve never heard anyone say anything like this before.

Teacher: That’s because it’s a bit alarming to hear it stated in such terms, even though it’s the most accurate way of describing it.

Student: What is it? What is this other world? Does it have a name?

Teacher: Yes. Your world, the modern world, is the immanent world. The other world is the transcendent world.

Student: And what’s your relationship to the transcendent world?

Teacher: As a classical teacher, I’m an ambassador of the transcendent world. My job is to present the transcendent world to you in such a way that you’ll want to take up residence there, be naturalized, and become a subject.

Obviously a conscious choice to use “subject” instead of “citizen” in the final sentence.

FOMO

Even the definition of FOMO itself has started to change. For millennials, FOMO meant fear of missing out on what was happening in the real world: physical experiences and events other people were enjoying. Now it seems to mean fear of missing out on what’s happening online: notifications, memes, group chats, TikTok trends, Snapchat Stories. For Gen Z, FOMO isn’t a harm of social media; it’s a motivation to use it. It’s what traps young people on TikTok and Instagram. They fear being left out of social media itself.

Freya India

The Free Academy

Sometime in the eighties, my brother Evan and I, together with some others, started something we called the Free Academy of Foundations. This was actually the precursor to New St. Andrews, and it was basically a reading list of great books—Dante, Augustine, Calvin, et al. This was not a list of books we had read, but was rather aspirational instead—books we thought we ought to read. I think I made it through the list, but if not, I read a bunch of those books at the time. That is where my real education started.

Shortly after that, we started offering classes at Evan’s house. These were basically community enrichment classes. They did not go anywhere, and non-matriculation was the name of the game. I remember teaching a logic course there, and Nancy also taught a course in English grammar. But this is where the name New St. Andrews was first applied. I think it was Evan who suggested the St. Andrews, and I thought we should attach the New. After I became a Calvinist in 1988, Evan and I parted company in such joint ventures, and we agreed that I could keep the name New St. Andrews. We began offering the kind of classes that would culminate in a degree in 1994.

Doug Wilson

I find it fascinating to trace the headwaters of the institutions that have shaped me (Logos School, NSA, etc.). It’s good to remember their small beginnings—for example, as community enrichment classes that went nowhere. Until they did.

Culture War is Necessary

The first issue of Good Work contains an article explaining the mission of the magazine. Man, that was tough to write. I wanted to reframe the terms of the “culture war” without a) throwing down my weapons or b) picking unnecessary fights. I’m not 100% sure I succeeded. Judge for yourself.

Or you could read this excerpt from Doug Wilson’s recent newsletter on education (paywalled, unfortunately). Leave it to Doug to say what I’m thinking more lucidly than I can.

Chesterton spoke wisely of the man who fights, not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him. And I have taught (for decades I have taught) that just as you cannot have a naval war without ships, or tank warfare without tanks, so also you cannot have culture war without a culture. And a culture is something you must inhabit, as one who loves his home, and so you must inhabit it as a dutiful citizen who is devoted to . . . culture care.

This means an essential part of culture care is fighting off invasions, and resisting predation. When the Germans conquered France, and were confiscating enormous stores of rich wines, culture care needed to include hiding wine from the Nazis, as in fact it did. But in order to do this, there would have to be some recognition of why they were needing to hide wine from the Nazis. Not to be too obvious about it, they were having to do this because of an invasion. There was a war on because someone was attacking. There was a culture war because someone was invading and seizing the cultural artifact—wine.

As he says, “you cannot have a culture war without a culture.” This means someone has to be plowing, sowing, watering, and harvesting to feed the man on the front lines. Good Work is that first guy.

The flaw in my analogy is that, in a real war, the farmer and the warrior are mutually exclusive. As long as the farmer’s planting, he’s not fighting. When he takes up his pitchfork to fight the bad guys, he has to ignore his fields for a bit. For Christians, good work, done to the glory of God, is an act of war. The man who cares for his family, goes to church, reads the Bible, sings the Psalms, and prays for his country is a culture warrior even if he never holds a picket sign. In other words, a faithful Christian life is always warlike, though it may not look like it from the outside.

You may have seen the video of Doug torching a bunch of cardboard cutouts with a flamethrower. Lots of people loved it. Lots of people hated it. But most of them ignored the most important part, which came near the beginning:

Here we footage from the front lines of the culture war. Want to do your part to demolish the city of man? Eat dinner with your family.

That said, there are times when Christians must behave like warriors in the conventional sense, when we must be belligerent and accept nothing less than victory. What if Martin Luther had been content to read Romans in the privacy of his own home (for the sake of not causing a fuss) and never challenged the authority of the pope? For that matter, what if the apostles had kept the news of the resurrection to themselves, so as not to ruffle any feathers? Sometimes, being a faithful Christian means picking a fight.

How do you know when to tend to the farm and when to grab your flintlock? Good question. We’re certainly living in times that require us to work through the answer.

Taming the Tongue

James’s writing on the tongue suggests that taming it is part of the dominion mandate:

For every kind of beast and bird, of reptile and creature of the sea, is tamed and has been tamed by mankind. But no man can tame the tongue. It is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison.

Even though he says here that taming the tongue is impossible, a few verses earlier he says this:

If anyone does not stumble in word, he is a perfect man, able also to bridle the whole body.

In other words, the perfect man rules himself as he rules horses (v. 3), ships (v. 4), and all other created things. I don’t think it’s going to far to say that self-governance is one of Adam’s original tasks.