Instagram in 1909

Robin Sloan is reading The Green Knight on New Years Day. I plan to read it over the Twelve Days of Christmas. That puts me in mind of other books I try to read at specific times of the year.

I wonder what other book/season pairings there are in my life. Maybe I’ll add Dandelion Wine to read over the summer.

I’m only a few chapters into Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, but already I’m convinced that the children have some of the best parents in literature.

As the author, I’m thrilled.

As the publisher, I’m trying to figure out how to get a rush order from China.

The most frustrating thing about Alan Jacobs’s blog is the lack of a comments section. He posts so many thought-provoking things, and then gives me nowhere to put my provoked thoughts. So, here, in no particular order, are a handful of my reactions and comments to various things he’s posted over the past few months.

This post may explain why I just can’t bring myself to worry about ChatGPT in education. I just can’t summon the panic:

Imagine a culinary school that teaches its students how to use HelloFresh: “Sure, we could teach you how to cook from scratch the way we used to — how to shop for ingredients, how to combine them, how to prepare them, how to present them — but let’s be serious, resources like HelloFresh aren’t going away, so you just need to learn to use them properly.” The proper response from students would be: “Why should we pay you for that? We can do that on our own.”

If I decided to teach my students how to use ChatGPT appropriately, and one of them asked me why they should pay me for that, I don’t think I would have a good answer. But if they asked me why I insist that they not use ChatGPT in reading and writing for me, I do have a response: I want you to learn how to read carefully, to sift and consider what you’ve read, to formulate and then give structure your ideas, to discern whom to think with, and finally to present your thoughts in a clear and cogent way. And I want you to learn to do all these things because they make you more free — the arts we study are liberal, that is to say liberating, arts.

Alan Jacobs

The things that I want to teach students have nothing to do with ChatGPT or other “fake intelligences.” Like Josh Gibbs, I’m actually rather pleased that such tools are revealing the mechanistic nature of so many assignments.

Here Jacobs argues that “it is virtually impossible for good art to be made in our place, in our moment” because we—addicted as we are to the Panopticon—are victims of self-censorship, which is the enemy of artistic expression. This dovetails with two other posts: this one on cultivating a quiet “home base” away from the censorious crowds, and—to push back on the idea of the self-sufficient artist—this one on the importance of intellectuals (and, I would add, artists) always having “a living community before their eyes,” that is, a group of people to whom their thoughts and words are directed.

Here’s Jacobs doing what he does best: making fascinating connections between books. His description of The City and the City reminds me of Descent Into Hell by Charles Williams, though in the latter the cities overlap in time, not in space.

This past summer I called Spectrum to see if they could lower the price of our internet service. Not only did they cut it in half, they threw in a free Galaxy tablet. It’s cheap as far as tablets go, but it has had a huge effect on my reading habits this year. Since I don’t really like reading books on the computer, I never really made use of the treasure trove that is the Internet Archive.1 For some reason, reading on a tablet doesn’t bother me as much, so I’ve been able to dive into all the books I can’t afford to buy. I prefer paper books, of course, as does any sane person, but it’s hard to argue with cheap. Books I read on the tablet are marked with a **double asterisk. One *asterisk means I read it on my Kindle.

Total: 68

In covering The Social Contract, we will do close reads of a few passages. Some of those passages will be easy and some will be hard. However, learning to speak philosophy requires not only the close work of interpretation but prolonged general exposure to it. Put another way, learning to read difficult books requires not only quality time but quantity time.

If there are long passages in today’s reading that you don’t get, don’t tell yourself, ‘I don’t get this book’ and give up. The truth is, you’re not going to get many parts the book, but this book is worth reading for the portions that you do get. If we didn’t cover the difficult parts, you would never get to a place that you could understand them.

Josh Gibbs

This is why, in my 7th grade Humanities class, I assign the entirety of the Odyssey.

This is the third of a series of posts about Dorothy Sayers’s essay “The Lost Tools of Learning.” I think that’s sufficient introduction for anyone who reads this blog. Here are the first and second installments.

Also, I’m going to call her Dottie throughout, because I want to.

Some in the world of classical Christian education disparage Dottie because of her emphasis on teaching the “tools of learning,” which the educated student can apply to anything he pleases. They insist that the quality of an education depends on what is taught as well as how it is taught, and they believe that Dottie’s approach doesn’t take this into account. True, Dottie is somewhat agnostic about content. She says that the teachers must look upon their classes “less as ‘subjects’ in themselves than as a gathering-together of material [her emphasis] for use in the next part of the Trivium. What that material is, is only of secondary importance.”

As we’ve seen already, Dottie comes close to contradicting herself at various places in the essay, and this may be one of those places. After all, she spends quite a lot of time talking about what should and shouldn’t be studied in the Grammar Stage. But I think the operative phrase in the quote above is “less as.” The teachers will teach subjects, truth, stories, facts, information, but they must see these things as all of a piece. Everything they teach can be used later on, which means nothing memorized is completely useless. It does not mean that the teachers should break advanced subjects into pieces and get the kids to memorize the pieces. But that will have to wait for another post. First, let’s look at Dottie’s curriculum recommendations for the Grammar Stage.

To master Grammar itself, students should learn the grammar of an inflected language. (This rules out English, as we saw earlier.) Dottie is ok with Russian, Sanskrit, and Classical Greek, but she recommends Latin—Medieval Latin, that is, not Classical. I don’t know of any classical school that starts with Medieval Latin, but that may be due to a lack of textbooks.

Dottie also suggests starting a contemporary foreign language at this age. She recommends French or German. Honest question: Do any classical schools teach modern languages in the Grammar Stage?

Dottie recommends memorizing (and reciting) poetry and prose and telling many, many stories, including ancient myths. Do not, says she, do not use ancient myths to practice Latin grammar. I suppose she doesn’t want young people to spend time poring over the unfiltered words of pagan authors.

I don’t want to point fingers, but I want to emphasize here that Dottie recommends History consist of dates, events, anecdotes, and personalities. Memorizing a timeline of dates and events does no one any good unless those dates and events are tied to real people and what they did. The particular dates, she says, don’t matter. What matters is having a historical framework of some kind—accompanied by “pictures of costumes, architecture, and other ‘everyday things.” Got that? Worry less about memorizing five hundred dates and more about getting a full picture of one or two historical time periods.

Geography, like history, is presented as facts associated with visual presentation: “customs, costumes, flora, fauna, and so on.” She encourages memorizing capitals and collecting stamps.

Dottie recommends teaching science through “the identifying and naming of specimens.” Notice that word “identifying.” How is a student going to identify a devil’s coach-horse, Cassiopeia, a whale, or a bat without observing them? There is nothing in her description of Science that would require a student to even be inside a classroom. Excursions into nature seem like an obvious extension of her suggestions.

I know people who scoff at the phrase “the grammar of Mathematics” because they view “grammar” as a linguistic term. But if we take Dottie’s own definition of grammar as “learning what language is, how it’s put together, and how it works,” then we can easily see how the term applies to math. She recommends memorizing multiplication tables, geometrical shapes, and “the grouping of numbers,” followed by simple sums in arithmetic. I’m not sure that these activities by themselves will result in a student’s understanding “what language is, how it’s put together, and how it works,” but then, I’m not sure that any of Dottie’s Grammar Stage recommendations fulfill that promise.

Here, more than anywhere else, Dottie emphasizes that the student does not need to fully understand the material, merely to be familiar with it. She recommends teaching the Biblical narrative as a complete story of Creation, Rebellion, and Redemption, as well as the Apostle’s Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments. I think she underestimates the students here. A nine-year-old can easily understand all of those things—not fully, perhaps, but sufficiently.

This is this week’s edition of Time’s Corner, my bi-weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

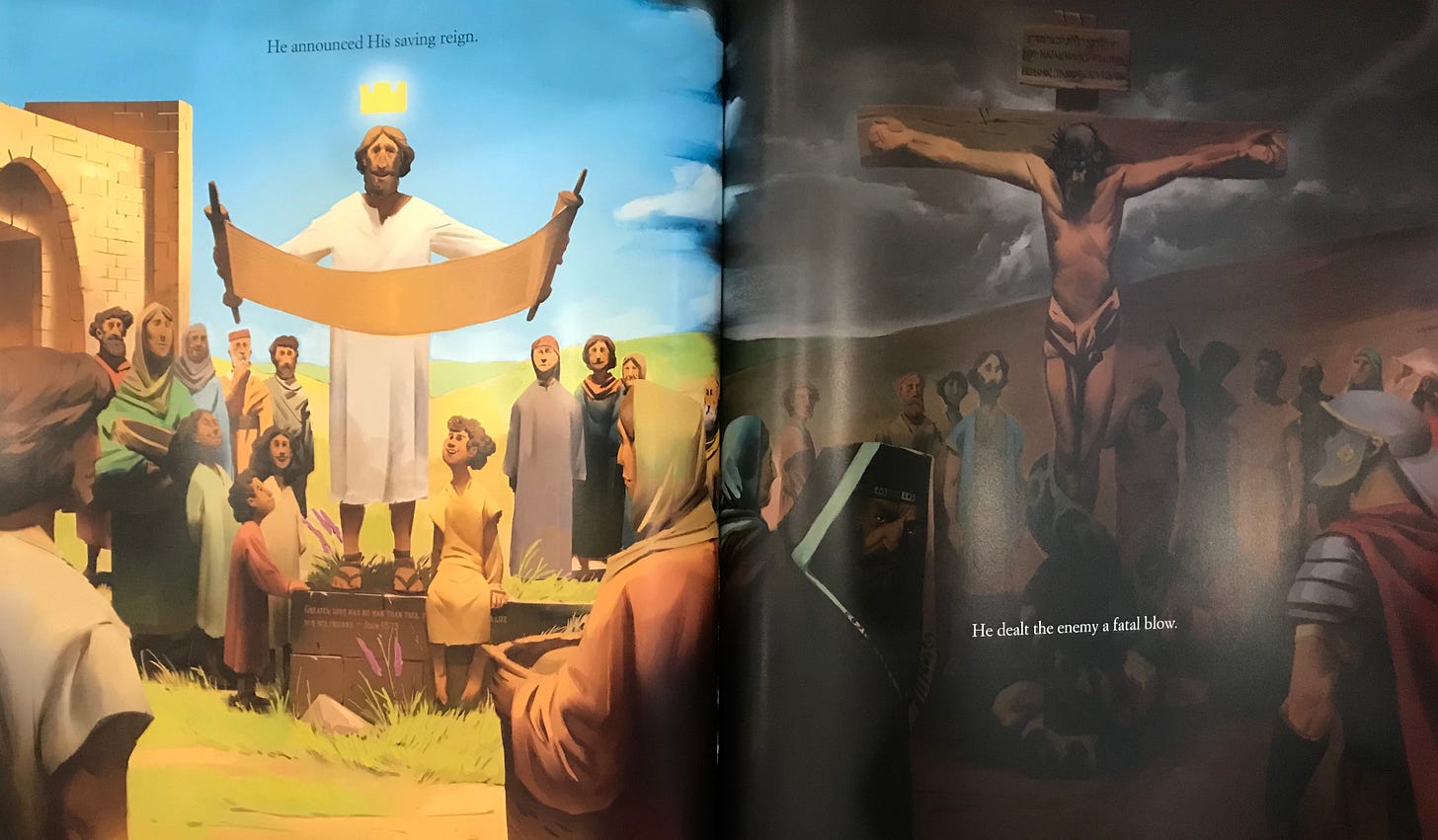

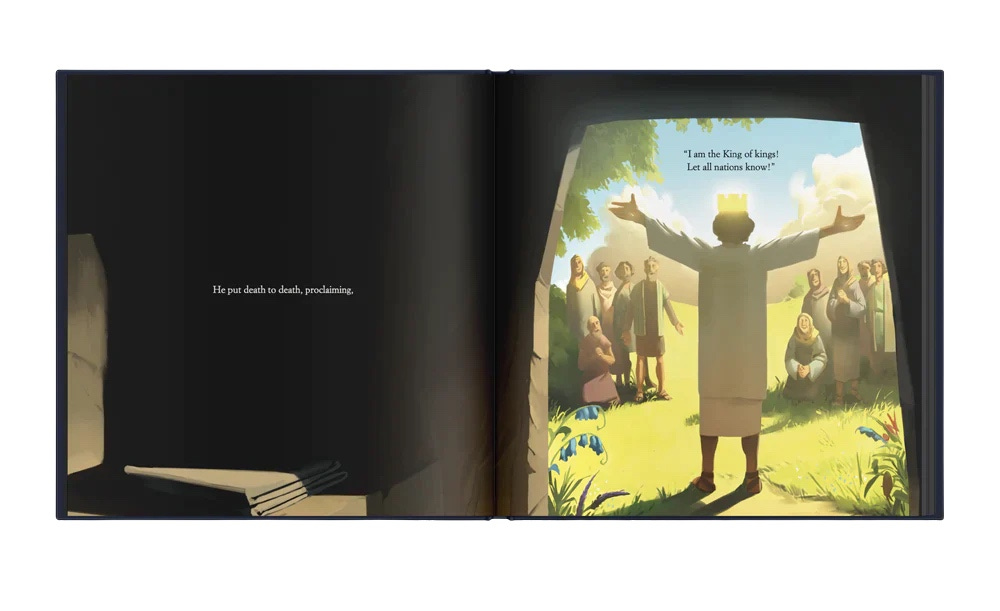

Behold! My friend Brian Moats and I have started a publishing company! It’s called Little Word. We create children’s books that teach Biblical symbols and patterns, particularly typological motifs. Read more on our website. (If you click on only one link today, make it this one.)

Years ago, I saw this posted on Twitter:

At the time, I had already toyed with the idea of creating a “Through New Eyes for Kids” book series, and when I saw this tweet, I realized a series like that would have an audience. I opened a notebook and started scribbling down ideas.

Later that same year, I happened upon Anne-Margot Ramstein’s picture book Before/After. There are no words in the book, nor any story. Instead, each page spread has two pictures side by side and you’re invited to figure out the connection between them. Despite the fact that there’s nothing to read or fiddle with, it’s one of the most interactive books I’ve ever read.

One of the most common connections between the two pictures is time—hence the name: Before/After. A beehive becomes honey. A jungle becomes a city. Sometimes, Ramstein highlights time’s cyclical nature. Day, night. Summer, winter. High tide, low tide. My favorite pages are where one object remains fixed while everything around it changes. Time acts more slowly on some things than others.

This struck me as powerful way to depict typology. Take Samson. Arms outstretched, one hand on each pillar, positioned in exactly the same way that Jesus was on the cross. Put Samson and Jesus on two facing pages and invite the reader to make connections between them. Even a child could do it—especially a child.

Aedan Peterson actually did something like this in Ken Padgett’s The Story of God Our King. Three sequential pages show Jesus in the same posture, arms oustretched, while the scene changes around him.

Pretty cool.

Meanwhile, in his home office, Brian had been editing hours upon hours of footage of Jim Jordan, Peter Leithart, Alastair Roberts, and Jeff Meyers talking about Biblical typology. He had taught youth Sunday school classes on Through New Eyes and The Lord’s Service and found his students extremely receptive to the ideas in those books. It was just a matter of time before Brian decided to adapt Jordan and Meyers for kids. He approached me about the idea and lo! Little Word was born.

I’ll keep you updated on our progress here at Time’s Corner, but the best way to stay informed is to follow Little Word on all the socials. Click for the ‘gram, the Tweetster, the Facity-Face, etc.

And my great wish is, that young people who read this record of our lives and adventures should learn from it how admirably suited is the peaceful, industrious, and pious life of a cheerful, united family, to the formation of strong, pure, and manly character.

Johann David Wyss, The Swiss Family Robinson