As the author, I’m thrilled.

As the publisher, I’m trying to figure out how to get a rush order from China.

As the author, I’m thrilled.

As the publisher, I’m trying to figure out how to get a rush order from China.

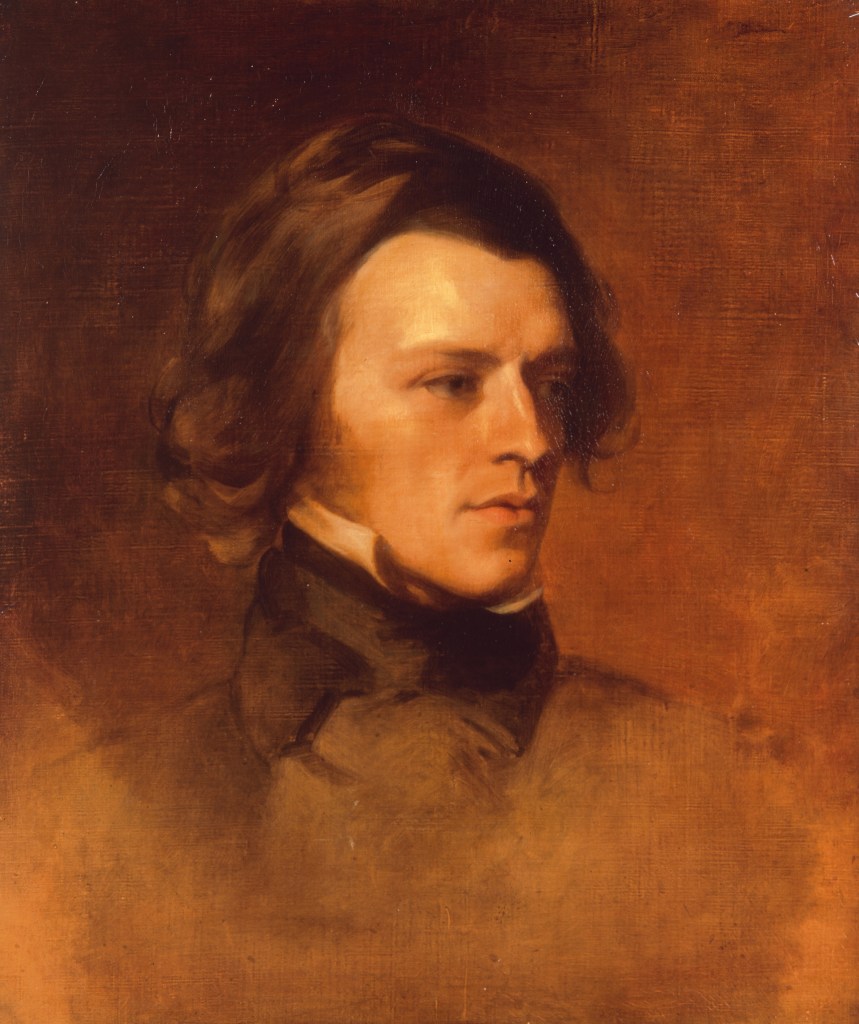

The essayist is a self-liberated man, sustained by the childish belief that everything he thinks about, everything that happens to him, is of general interest. He is a fellow who thoroughly enjoys his work, just as people who take bird walks enjoy theirs. Each new excursion of the essayist, each new “attempt,” differs from the last and takes him into a new country. This delights him. Only a person who is congenitally self-centered has the effrontery and the stamina to write essays.

E. B. White

The naked eye—

Do you see him, antlered there,

Part shadow and part briar,

His foreleg feeling out the air,

Cautious, stepping, tense as wire,

Dappled, out into the glade?

The magnifying glass—

Look, his nostrils storm with ticks

And blackflies lash his eyelids—

Mangy haunches, antlers split,

Limping, fleetness checked by pallid

Illness barely kept at bay.

The microscope—

Insect bodies glow like naves

With stained glass in their chapels,

While microbes deck the cloistered caves,

A riot spotted, prismed, dappled—

Beauty even in decay.

Adventure requires courage to keep us faithful to the struggle, since by its very nature adventure means that the future is always in doubt. And just to the extent that the future is in doubt, hope is required, as there can be no adventure if we despair of our goal. Such hope does not necessarily take the form of excessive confidence; rather, it involves the simple willingness to take the next step.

From Stanley Hauerwas, “A Story-Formed Community: Reflections on Watership Down“

(No, not Brian De.)

I find myself intrigued by the BOOX Palma after reading Craig Mod’s enthusiastic description “A one-handed reading wonder?” With an e-ink screen that operates smoothly? Yes, please.

The spine is black with white or yellow letters

That have those little hands and feet called “serifs.”

About the height of a new pencil

And the width of my index finger,

It has a hammer on the cover

And the word “Poetry” in the title…

No? I’ll have to ask another poem then.

The most frustrating thing about Alan Jacobs’s blog is the lack of a comments section. He posts so many thought-provoking things, and then gives me nowhere to put my provoked thoughts. So, here, in no particular order, are a handful of my reactions and comments to various things he’s posted over the past few months.

This post may explain why I just can’t bring myself to worry about ChatGPT in education. I just can’t summon the panic:

Imagine a culinary school that teaches its students how to use HelloFresh: “Sure, we could teach you how to cook from scratch the way we used to — how to shop for ingredients, how to combine them, how to prepare them, how to present them — but let’s be serious, resources like HelloFresh aren’t going away, so you just need to learn to use them properly.” The proper response from students would be: “Why should we pay you for that? We can do that on our own.”

If I decided to teach my students how to use ChatGPT appropriately, and one of them asked me why they should pay me for that, I don’t think I would have a good answer. But if they asked me why I insist that they not use ChatGPT in reading and writing for me, I do have a response: I want you to learn how to read carefully, to sift and consider what you’ve read, to formulate and then give structure your ideas, to discern whom to think with, and finally to present your thoughts in a clear and cogent way. And I want you to learn to do all these things because they make you more free — the arts we study are liberal, that is to say liberating, arts.

Alan Jacobs

The things that I want to teach students have nothing to do with ChatGPT or other “fake intelligences.” Like Josh Gibbs, I’m actually rather pleased that such tools are revealing the mechanistic nature of so many assignments.

Here Jacobs argues that “it is virtually impossible for good art to be made in our place, in our moment” because we—addicted as we are to the Panopticon—are victims of self-censorship, which is the enemy of artistic expression. This dovetails with two other posts: this one on cultivating a quiet “home base” away from the censorious crowds, and—to push back on the idea of the self-sufficient artist—this one on the importance of intellectuals (and, I would add, artists) always having “a living community before their eyes,” that is, a group of people to whom their thoughts and words are directed.

Here’s Jacobs doing what he does best: making fascinating connections between books. His description of The City and the City reminds me of Descent Into Hell by Charles Williams, though in the latter the cities overlap in time, not in space.

Nieman Storyboard has an ongoing series called “Why’s This So Good?” in which they analyze writing to find out why it’s, you know, so good. When I read this short section of an article by Ed Ruscha describing his burning desire for white jeans, I couldn’t get it out of my mind. This is me trying to figure out why.

In 1951, when I was fourteen, I landed a job in an Oklahoma City laundromat. The pay was respectable–fifty cents an hour, up from forty-five. In a swampy, bunkerlike back room with a large concrete center drain, I had to mix bleach and water together in brown glass bottles for the customers to use. It was sweaty and dank, but I got to listen to a faraway radio, faint but distinct, playing music by the likes of Lefty Frizzell, Hank Williams, and Faron Young.

One day, I saw a news item about the murder of a nurse in Ann Arbor, Michigan. A photograph of one of the teenage killers showed him in handcuffs, being escorted by police. He was wearing what looked to me like white Levi’s. White Levi’s! What style! I was overcome by an immediate urge to get a pair for myself, but after looking around I was told that no such product existed–at least, not in Oklahoma.

Then it came to me: I would make my own. I brought a pair of bluejeans from home, doused them in undiluted Clorox bleach, and placed them in a washing machine. I let them sit for half an hour, the mystery and suspense building. When I finally opened the door, I found, to my astonishment, a pair of pure-white, radiantly glowing Levi’s. A triumph.

Or so I thought. Reaching in to grab them, I felt my hand sweep through a puffy lump of dead white fibres, softer than cotton candy. The rivets and the buttons were the only parts that survived.

At the time, I was banking on white Levi’s coming into fashion. I had to wait twenty years to buy a pair off the rack.”

Ed Ruscha via Put This On

If I were to tell this story to a friend, it would go something like this: “I wanted a pair of white jeans once. I couldn’t find them for sale anywhere, so I decided to bleach some normal blue jeans, but when I did, they melted.”

The strength of Ruscha’s writing here mainly comes from the specific details, obviously. Just to make sure, here it is with the specifics removed:

In 1951, I landed a job in a laundromat. The pay was respectable. In a back room, I had to mix bleach and water together in glass bottles for the customers to use. It was unpleasant, but I got to listen to a radio.

One day, I saw a photograph in a newspaper of a man wearing what looked to me like white Levi’s. I wanted a pair for myself, but after looking around I was told that no such product existed.

Then I decided I would make my own. I brought a pair of bluejeans from home, doused them in bleach, and placed them in a washing machine. When I finally opened the door, I found, to my astonishment, a pair of pure-white Levi’s.

Or so I thought. Reaching in to grab them, I discovered they had disintegrated in the bleach and were ruined.

Here’s what I removed:

Et cetera.

A good sample to reference if your descriptions are falling flat.