What is “Tech?”

Once upon a time, the word “technology” might have been applied to something such as a new design element that reduces frictional losses in a gear set. Today, the word is often shortened to “tech” and it typically means: finding new ways to insert a layer of fussiness into some aspect of life that is not yet subject to

Matthew Crawfordfussiness“optimization”, and then collecting rents from the friction this introduces.

Responsibility and Challenge

This is Monday’s edition of Time’s Corner, my bi-weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

In the last issue of TC, I made the claim that three ingredients necessary to a boy’s education are teamwork, responsibility, and challenge. I’m not saying that including these three ingredients will solve all the problems that exist in modern schools. I’m merely observing the boys I interact with day to day and trying to understand why they find sports so much more attractive than academics. In other words, is there a way to make a boy care about school?

Some of you reading this will say, “A school shouldn’t cater to a boy’s tastes. The school should shape the boy’s tastes.” I agree with both statements, but I think it’s a false dichotomy. The rules of basketball don’t bend according to the players’ whims, but a good coach will study his players and adjust his practices according to their abilities. My question is not, “What does a boy need to learn?” but “How do we help him learn what he needs to learn?”

I had originally planned to write this in three installments. The first installment was several weeks ago, and so, to prevent what was meant to be a short series from going on forever, I’m going to cram Installments 2 & 3 into this issue. And by cram, I mean make one very succinct point. You’re welcome.

Responsibility

If W. H. Auden had ever founded a “College for Bards,” which he sometimes daydreamed about, the curriculum would have included not only reading, writing, and memorizing, but also care for domestic animals and garden plots. I suspect that he thought interacting with the natural world would help a budding poet be a little less of a fathead.

I like his idea, and not just for poets. Anyone who spends most of his time engaged in intellectual work needs to get out in the fresh air every once in a while. Working with your hands reminds you that the world does in fact exist and, what’s more, it doesn’t exist to please you. In Matthew Crawford’s book Shop Class as Soul Craft, he says, “The moral significance of work that grapples with material things may lie in the simple fact that such things lie outside the self.” In other words, you aren’t the center of the universe. Everybody needs to learn that at some point, boys perhaps most of all.

This is where responsibility comes in. Put a boy in charge of another living creature and he must choose between helping it thrive or letting it shrivel. Either way, he must do something. That’s an important lesson, and if the boy does his job, the school gets fresh vegetables besides.

Challenge

A long time ago, the word “challenge” basically meant a false accusation, or rather an accusation that a person would have to defend himself against. To “rise to the challenge,” then, could mean something along the lines of “prove ‘em wrong.” You’ve been called a coward. Prove ‘em wrong. You’ve been accused of theft. Prove ‘em wrong. Though we now use the word to mean “a difficult task,” it still carries an element of risk, a sense that something is on the line. If you succeed in overcoming a challenge, you will be justly praised. If you fail, you lose more than whatever goal you were reaching for. You lose the faith others have placed in you.

When you issue a challenge to a group of boys, many of them will take it as a test of their manhood. Boys take every opportunity to prove their manhood to themselves and to others, often without even thinking about it. “At any moment of a man’s life,” says Anthony Esolen in his book Defending Boyhood, “his manhood is subject to trial, to be won, again and again, to be confirmed or to be canceled. A man can lose forever his right to stand beside other men. He can fall to being no man at all.” Boys take their own measure (and that of their peers) against the standard of manhood, and issuing a challenge is like calling them babies and then saying, “Prove me wrong.”

Once again, I’m merely guessing here, but I have a hunch that many boys have never felt the gut-wrenching need to rise to and repudiate a challenge that was issued to them by a teacher. Rarely is there anything at stake other than their own financial future, which, let’s face it, most boys assume will take care of itself. In sports, the challenges and outcomes are very clear: you either win or lose. In academics, failures are more private and even somewhat relative. A student can work half-heartedly and still pass.

To make a boy do his best, the teacher should challenge him. But how? What would make a young man feel as though what he did in the classroom actually mattered? I’m still mulling over this one.

The Compleat Cockroach

Reading this for my own sanctification.

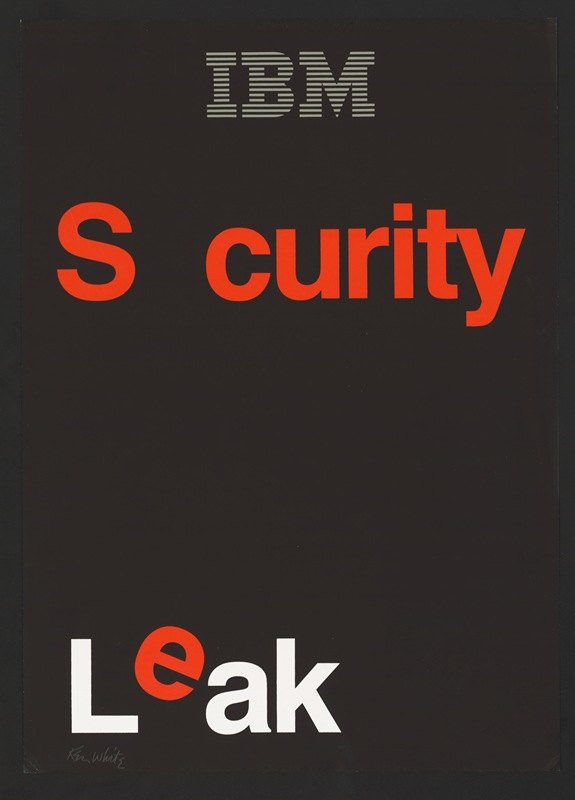

Ken White Designs

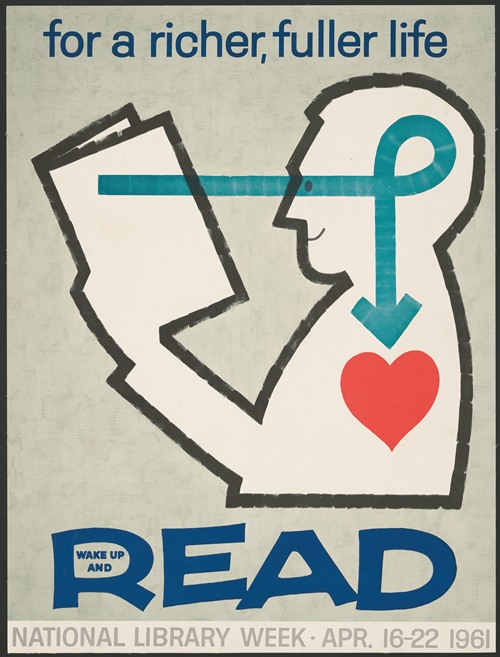

Wake Up and Read

Books and Children

It occurs to me that everything that can be said against the inconvenience of books can be said about the inconvenience of children. They too take up space, are of no immediate practical use, are of interest to only a few people, and present all kinds of problems. They too must be warehoused efficiently, and brought with as little resistance as possible into the Digital Age.

Anthony Esolen, Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child

Blog Museum

This reminds me of an idea I’d still like to see put into practice: a service that pulls posts from old blogs and collects them into a daily digest. I love reading blogs, especially old ones. Scrolling through a bunch of posts from the same author, sometimes written over the course of years, is like reading their journal. It gives you a picture of that writer’s personality and the ideas they’ve wrestled with over the years. It would be exciting to be reminded every so often that such an archive exists.

Or, One Might Say, for Good Work

The present is a time not for ease or pleasure, but for earnest and prayerful work.

J. Gresham Machen, Christianity and Liberalism

Subscribe to Good Work here.

To Feel How Feeling Feels

Being low to the ground is core to childhood. Children like to talk about worms; they live in a world of dirt and asphalt, their hands are always wet. Their mental life evolves in light of the nearness of the corporeal world, the world of things. Their nursery rhymes tell stories about beasts and wood. Their classrooms are festooned with images of animals, abstracted, made palatable for young eyes. Their world is visceral and new. They touch things just to touch them, to feel how feeling feels.

Freddie deBoer