In the last several years, it has become common to hear about the importance of being a “lifelong learner.” While the first time I ever heard the phrase was in the context of classical education, I have since learned it derives from the world of TED talks and corporate virtue signaling. If one considers the term for a moment, it becomes suspect. A lifelong learner of what? In and of itself, learning has no moral value. Learning can be good or bad. Eve learned quite a lot when she ate of the fruit. In the dark corners of the internet, one may learn all sorts of wretched and destructive things. But in the pages of Scripture, we can learn of Christ and be saved. In the pages of old books, we can learn wisdom.

Josh Gibbs

Learning is not virtuous unless one is learning virtue.

What is more, acting as if it is an accomplishment to be a “lifelong learner” sets the bar ridiculously low. The modern man lives in a deluge of information where he is constantly hearing trivial facts, lurid stories, and inconsequential data. We browse the internet every day, we read the news every day, we watch banal documentaries on Netflix all the time, and then we forget most what we learned because it wasn’t important or because it asked nothing of us. Simply put, we’re already lifelong learners. Lifelong learners need nobler, higher, and more definite ambitions.

Author Archives: cleithart

Drab Utilitarianism

I’m making my way through J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism and will be posting some of my notes here. Describing the woeful tendency of liberalism to quash all higher aspirations in favor of “drab utilitarianism,” Machen gives this example:

In the state of Nebraska, for example, a law is now in force according to which no instruction in any school in the state, public or private, is to be given through the medium of a language other than English, and no language other than English is to be studied even as a language until the child has passed an examination before the county superintendent of education showing that the eighth grade has been passed. In other words, no foreign language, apparently not even Latin or Greek, is to be studied until the child is too old to learn it well. It is in this way that modern collectivism deals with a kind of study which is absolutely essential to all genuine mental advance. The minds of the people of Nebraska, and of any other states where similar laws prevail, are to be kept by the power of the state in a permanent condition of arrested development.

Machen, Christianity and Liberalism

What is curious about this example is that it is the exact opposite of what today’s liberal would advocate. Public school teachers and boards in many states are strong proponents of teaching in multiple languages, especially Spanish, and of striking down English-only laws. I can’t imagine a law being passed that would prevent a school from teaching a non-English language before eighth grade. (In fact, the law Machen refers to was revoked in 1923, the same year Christianity and Liberalism was published.)

How can it be that what Machen saw as an example of liberalism would now be seen as an example of extreme conservatism? My guess is that he would argue that A) is it still utilitarian (bi-lingual education results in higher achieving graduates, which results in higher achieving citizens, etc.) and B) that both banning and requiring multiple languages in school are examples of the state meddling in the private affairs of citizens.

The IMDb app

You may not know that the IMDb iOS app lets you sort lists by where they are currently streaming. For a long time, Instantwatcher.com was where I went to find out whether anything worthwhile was available on Netflix or Amazon. The IMDb app is way better. Let’s say you’re a huge Spielberg fan. Go to his filmography page and tap Streaming at the top. You’ll see a list of all sites that are currently streaming anything by Spielberg. Here are some screenshots to illustrate.

If These Be Not Truths

“Even if there be no hereafter, I would live my time believing in a grand thing that ought to be true if it is not. And if these be not truths, then is the loftiest part of our nature a waste. Let me hold by the better than the actual, and fall into nothingness off the same precipice with Jesus and Paul and a thousand more, who were lovely in their lives, and with their death make even the nothingness into which they have passed like the garden of the Lord. I will go further, and say I would rather die forevermore believing as Jesus believed, than live forevermore believing as those that deny Him.”

~ George MacDonald, Thomas Wingfold, Curate

Puddleglum must have been a MacDonald fan, according to what he says to the Queen of Underland:

Suppose this black pit of a kingdom of yours is the only world. Well, it strikes me as a pretty poor one. And that’s a funny thing, when you come to think of it. We’re just babies making up a game, if you’re right. But four babies playing a game can make a play-world which licks your real world hollow. That’s why I’m going to stand by the play world. I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I’m going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia.

The Silver Chair (via Goodreads)

(MacDonald quote via Alan Jacobs)

More on Jacobs

Alan Jacobs has not responded to my post (the nerve!), but in an attempt to treat him as fairly as possible, I draw your attention to this post about his love for Jesus — or perhaps more accurately, Jesus’s love for him.

Every day I want to evade him, to look the other way, and when I do my faith wanes and weakens; but when I look, when I draw near, I remember what I’m all about, what the world is all about. When I look towards Jesus I am caught and held, even if sometimes shattered by what I see.

How to Treat a Book

Some books are to be treated courteously, others graciously, and some few to be embraced and surrendered to.

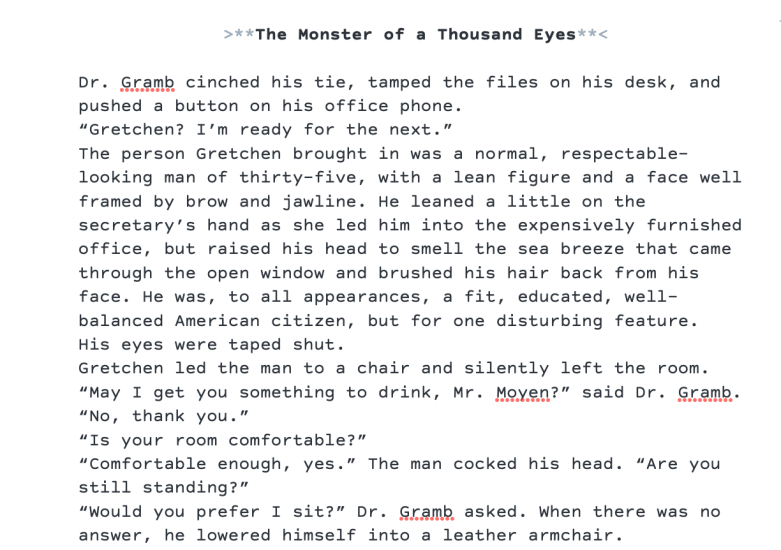

Writing Software

Except when forced to do otherwise, I use Highland or Highland 2 to write screenplays. Recently, I’ve been using it for rough drafts of all documents because it’s fast and doesn’t have as many bells or whistles as, say, MS Word. I’m not sure I like it, though. It works for screenplays because you what you see in the document is more or less what you’ll see on the page.

Visualizing my writing on the page helps me imagine the reader, which helps me make small adjustments to clarify whatever I’m trying to get across. Articles and stories, however, look very different in the Editor than they do in the Preview.

Not being able to see the page makes me write faster, but less coherently. At some point in the writing process, I switch over to whatever word processor I’ll use to make the final adjustments. Lately, I’ve been making the switch sooner.

Alan Jacobs and the Bible

If you’re no stranger to me, you’re no stranger to Alan Jacobs. I’ve only met him in person once or twice, but I read everything he posts on his blog and his essays when I have time. His book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction was jammed so full of reading recommendations, I almost started it again as soon as I finished. Reading a book or essay by Dr. Jacobs sometimes feels like watching a juggler perform. He has an amazing ability to weave multiple literary ideas into a coherent pattern, and just when you think you’ve been impressed, he brings in another book and sets it whirling. I would love to take a class from him.

Christian people, books, and ideas appear frequently, almost inevitably, in Dr. Jacobs’s writing, but he rarely talks about what it means to live as a Christian or what standard a Christian ought to operate by. When he does, I often find myself cocking my head and going, “Huh.” In one post, which I can’t find right now, he said that his Christianity informs his life hardly at all, a statement to which the only right response is, “That doesn’t sound like Christianity.” After reading many similar posts over the years, I have come to the conclusion that my main issue with Dr. Jacobs is not so much a quibble over theology as it is a disagreement over the Bible. In a recent post, he says this:

It’s also fascinating to note how little the apostles understand the message they been entrusted with. They know that Jesus is the Christ, the promised Messiah of Israel, and they know that the Christ’s own people rejected him and demanded his death – but beyond that they’re a little fuzzy about what the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus mean. The idea that what Jesus offers them (and all of us) is God’s limitless grace is rarely mentioned. It’s there, but only in tentative and vaguely articulated form.

I didn’t pick this post because it’s particularly egregious, only because it’s recent. He makes an interesting point about the psychology of the apostles, but then he says, “They’re a little fuzzy about what the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus mean.” I assume Dr. Jacobs is saying that Peter and the rest had only a vague understanding of God’s grace until Paul fleshed it out for them.

I’m not opposed to the idea that God’s people gain understanding over time. Just think of the wealth of commentary and tradition built up over the past two thousand years. In many ways, the church fathers were, in fact, church babies. My disagreement, I think, is actually a different stance toward the historical figures in the Bible. I assume that the words, decisions, and actions of the people of God are right, unless Scripture explicitly says otherwise. The zeal of the apostles post-Pentecost was not wrong or even misguided. Even the zeal of Apollos was not wrong, though his did have to be redirected (Acts 18:26). When we read the book of Acts, we shouldn’t assume we know something Peter doesn’t. Instead of smiling indulgently at his cute naivete, we should ask ourselves why the apostles spent so much time preaching Jesus as Messiah, rejected by His own people. Surely there’s an explanation beyond “They didn’t know any better.” We should be humble and charitable in our interpretation, a position Dr. Jacobs would certainly support in other contexts.

As I said, this particular example doesn’t bother me that much. But it does reveal something about the way Dr. Jacobs views the Bible, which is the view of most American evangelicals (I believe Jacobs is Anglican, which makes him evangelical, I think?). According to this common view, the Bible is a historical record of how human beings fail. Everything from Genesis to Jude describes God’s attempts to communicate lovingly and graciously and being given constant cold shoulders. Jesus came to save us despite our best attempts to ignore Him. As Dr. Jacobs’s friend Francis Spufford puts it, we all have the Human Propensity to F*** Things Up, and without Christ, not one of us could stand. So far, so orthodox. But this view gives rise to a rather awkward question: If the Bible is nothing more than a record of human failure, why is it so long? Couldn’t we have a few chapters here and there (the Fall, David and Bathsheba, the book of Amos) and then cut straight to Jesus? Evangelical Christians seem remarkably uncurious about the Bible and what it has to do with their everyday life.

It’s true that the actual people in the Bible did not know the full picture — Eve thought Abel was the promised seed (Gen. 4:25) — but that doesn’t mean that the full picture wasn’t present. The whole Bible is one prophetic book, not created by the will of man, but by the movement of the Holy Spirit (2 Peter 1:21), which means God’s limitless grace is as present in the story of the Flood as it is in the letters of Paul. That means the Flood story is still important and we need to study it. We don’t forget the candles just because the sun has risen. Candlelight is light, and remembering how it held back the darkness helps us understand the nature of the sun.

The thing that makes me nervous is how often Christians who doubt the power and wisdom of the Bible, especially the Old Testament, quickly drop other points of Christian dogma. They become squiffy on Creation, on biblical chronology, on Christian economics, on politics, on marriage, on the ordination of women, on abortion, ad inferna. Jesus doesn’t talk about most of these things, after all, and Paul can be controversial, which leaves us wandering through the philosophers, picking out whatever strikes our fancy (and won’t get us in too much trouble). The only antidote to such theological cherry-picking is embracing the wisdom of the whole Bible, whether the embrace makes us uncomfortable or not.

Despite our disagreement, I value Dr. Jacobs’s writing highly and hope he continues to poke his finger in all the right eyes (including conservative ones). I should also mention that he doesn’t easily fit into any camp, and if somehow this blog post swims into his ken, he may very well take issue with the way I’ve presented him. He will do so kindly, I’m sure.

All that said, I urge him to find a solid book on biblical theology and spend some time reading it as charitably as possible. (Here’s a good one.)

O Father You are Sovereign

Like most hymns, this by Margaret Clarkson doesn’t make for great reading by itself:

1 O Father, you are sovereign

in all the worlds you made;

your mighty word was spoken,

and light and life obeyed.

Your voice commands the seasons

and bounds the ocean’s shore,

sets stars within their courses

and stills the tempest’s roar.

2 O Father, you are sovereign

in all affairs of man;

no pow’rs of death or darkness

can thwart your perfect plan.

All chance and change transcending,

supreme in time and space,

you hold your trusting children

secure in your embrace.

3 O Father, you are sovereign,

the Lord of human pain,

transmuting earthly sorrows

to gold of heav’nly gain.

All evil overruling,

as none but Conqu’ror could,

your love pursues its purpose–

our souls’ eternal good.

4 O Father, you are sovereign!

We see you dimly now,

but soon before your triumph

earth’s ev’ry knee shall bow.

With this glad hope before us,

our faith springs up anew:

our sovereign Lord and Savior,

we trust and worship you!

There is one line, however, that jumped out at me as I sang this in church a few months ago. I put it in bold above. “Chance” and “change” make a nice pair, but combined with the syllables of “transcending,” it’s quite arresting. (I might alter is to “All change and chance transcending” to make it less of a tongue-twister. But sometimes tongues need to be twisted.)

I also like the use of “transmuting” in the third stanza. There’s not much science, pseudo or otherwise, in hymns. Although I think the language of hymns should be drawn from the Bible, it would be fun to sing about quarks and leptons occasionally.

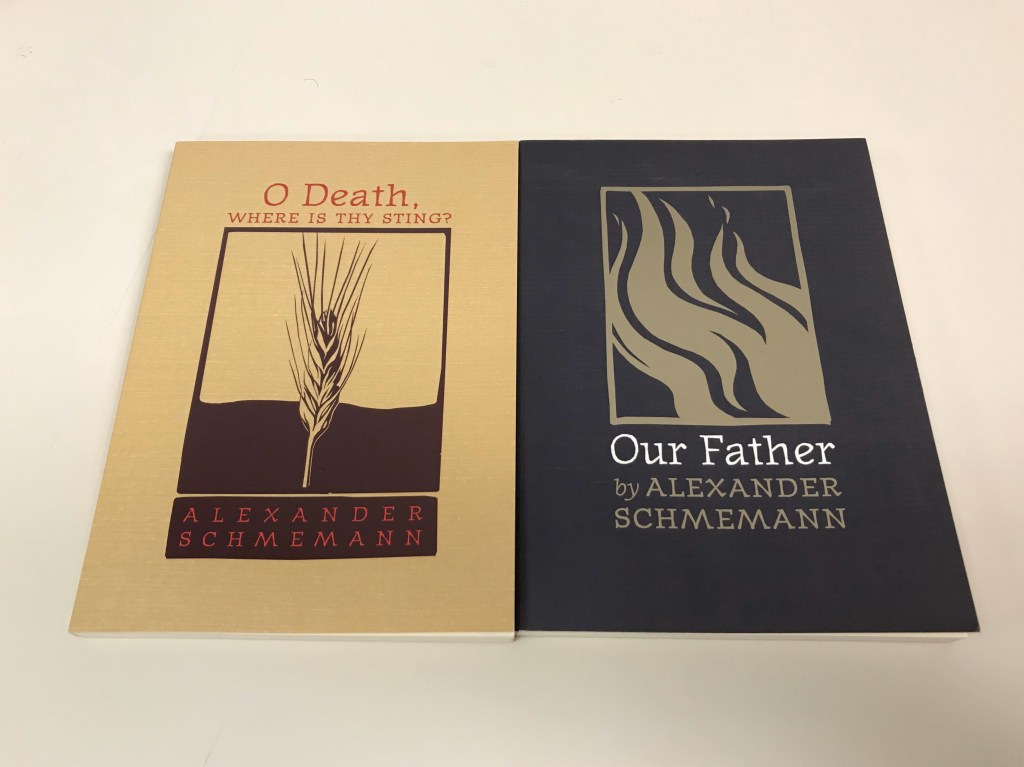

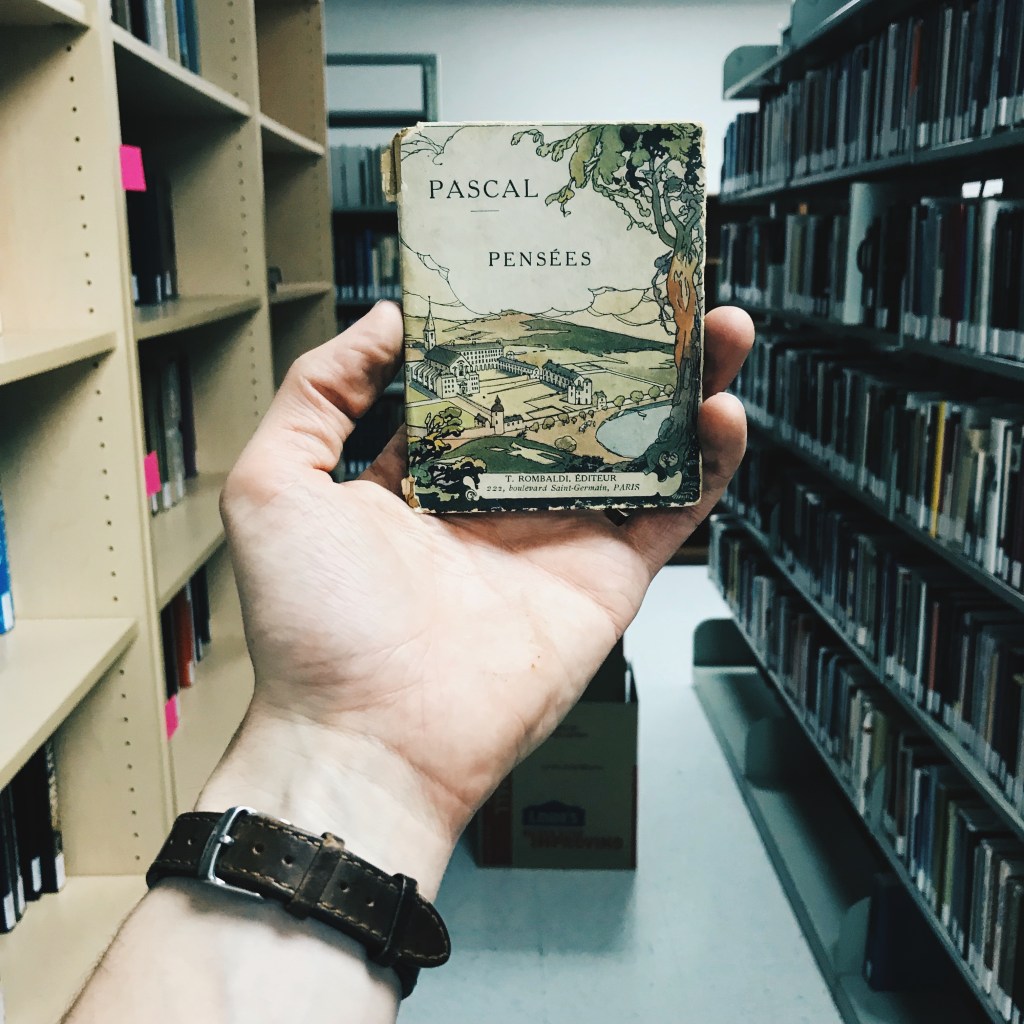

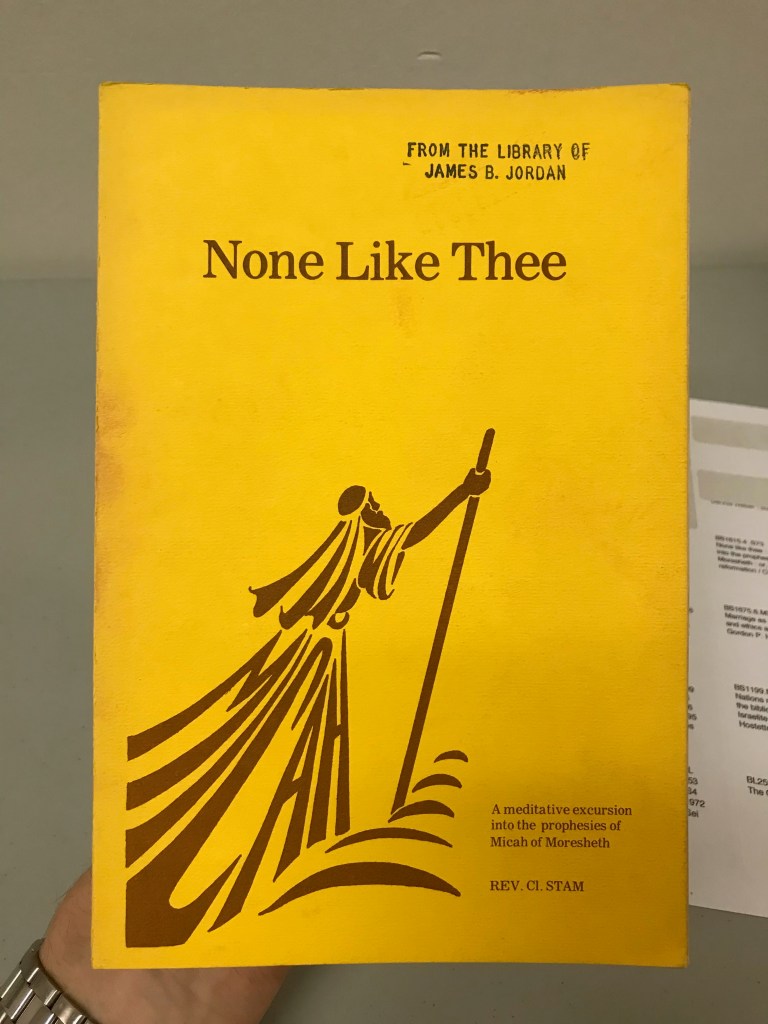

Book Covers I Like

A few years ago I was cataloguing the library of an eminent theologian, and I started to take pictures of the most interesting book covers. Here you are.

Processed with VSCO with hb2 preset

It wasn’t so much the cover of this one as the note inside.