This past summer I called Spectrum to see if they could lower the price of our internet service. Not only did they cut it in half, they threw in a free Galaxy tablet. It’s cheap as far as tablets go, but it has had a huge effect on my reading habits this year. Since I don’t really like reading books on the computer, I never really made use of the treasure trove that is the Internet Archive.1 For some reason, reading on a tablet doesn’t bother me as much, so I’ve been able to dive into all the books I can’t afford to buy. I prefer paper books, of course, as does any sane person, but it’s hard to argue with cheap. Books I read on the tablet are marked with a **double asterisk. One *asterisk means I read it on my Kindle.

Read-Alouds (10)

- Little House in the Big Woods, Laura Ingalls Wilder – I was freshly impressed with the descriptions in this book. And the last paragraph was unexpectedly poignant:

- “She was glad that the cosy house, and Pa and Ma and the fire-light and the music, were now. They could not be forgotten, she thought, because now is now. It can never be a long time ago.”

- More Milly-Molly-Mandy, Joyce Lankester Brisley – Cute, from what I remember.

- Stuart Little, E. B. White – My daughter loves stories about tiny people right now (The Borrowers, The Littles, The Indian in the Cupboard), so she was fascinated by Stuart. When I was young, I enjoyed Stuart Little for the same reason. I was always bothered by the end, though, when Stuart throws a massive tantrum and ruins any chance of friendship he has with the girl. And there’s the weirdness of the invisible car. And his massive crush on that bird! Man, what an odd book.

- The Swiss Family Robinson, Johann Wyss – This was a tough one to read aloud. So many long descriptions with relatively little dialogue or action. I think we have an abridged version around here somewhere. I’d recommend going with that.

- The Tale of Despereaux, Kate DiCamillo – Despite what you may have heard, this book is very much meh. It tries to be profound, but ends up being neither here nor there. I would have happily given it away, but my daughter adores it and reads it all the time.

- The Last Battle, C. S. Lewis – I hesitated to read this to my six-year-old and probably should have listened to those instincts. By the time we got to the last few chapters (the happily-ever-after), she was pretty much checked out.

- The Hobbit, J. R. R. Tolkien – Another difficult one for a six-year-old to sit through. I found it funnier than I had before (especially grumpy old Gandalf, which for some reason I pronounce “Gand-awlf” in real life, but “Gand-alf” when I’m reading).

- Freddy and the Spaceship, Walter R. Brooks – The Freddy books are so good. Seek them out and read.

- The Indian in the Cupboard, Lynne Reid Banks – Once, when asked for writing advice, Joss Whedon said, “Play your cards early. It forces you to come up with new cards.” This book is a perfect example of that storytelling strategy. Omri (what a name) only keeps the Indian secret for a few chapters before his friend Patrick finds out, and Patrick spills the beans a few chapters later.

- The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, Joan Aiken – Another favorite. I’d love to read more Aiken, but I have trouble finding her books.

Children’s Fiction (10)

- *William Again, Richmal Crompton – Recommended by Alastair Roberts. A rascally young boy gets into all kinds of scrapes. It’s hard not to like William’s straightforward nature, even though he would be intolerable in real life.

- The Westing Game, Ellen Raskin – Evergreen. Happy fourth of July.

- **The Story of a Short Life, Juliana Horatia Ewing – Sometimes I make forays into old children’s literature, hoping to find a gem. This one wasn’t.

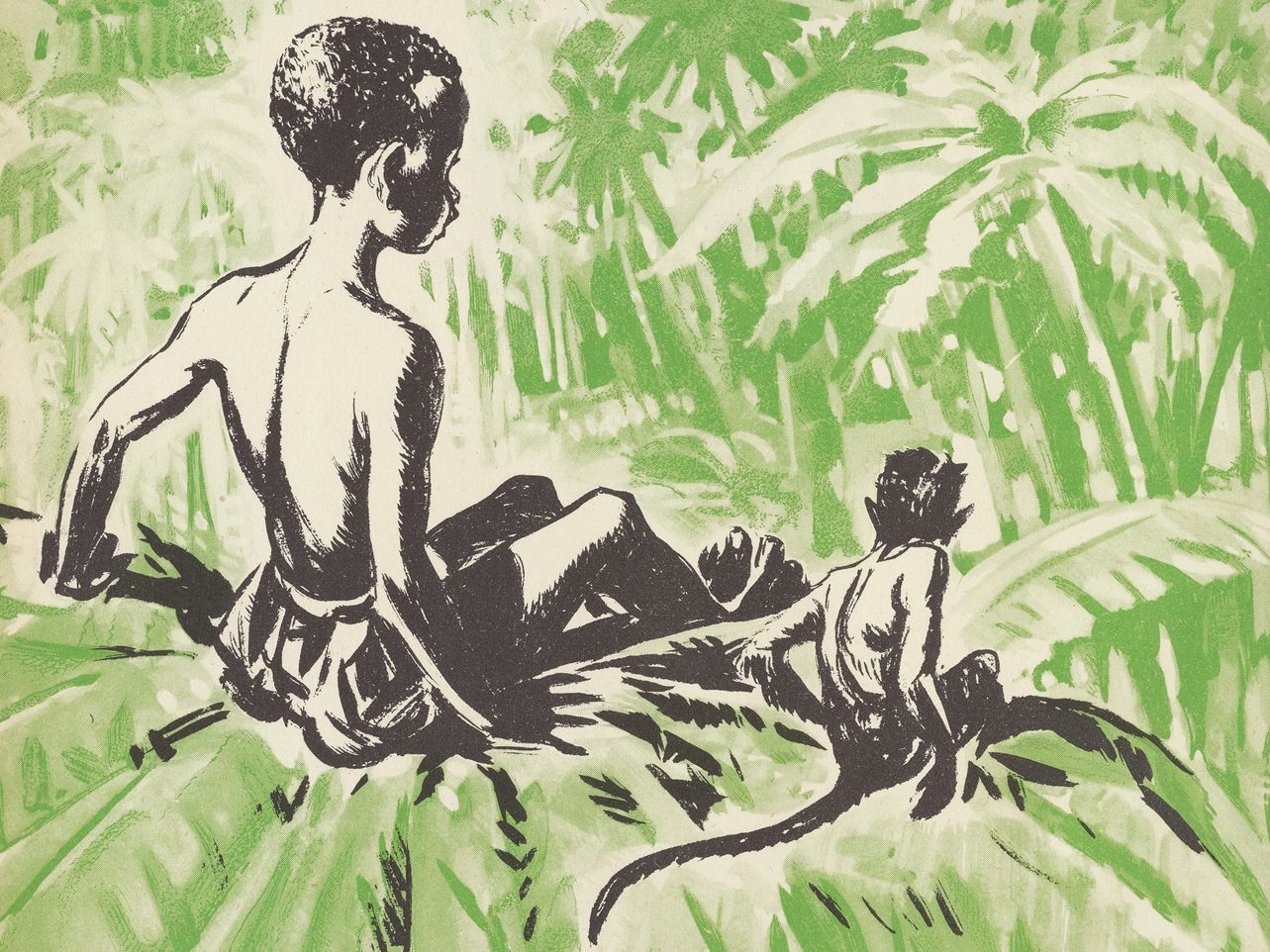

- **Picken’s Exciting Summer, Norman Davis – A fun, simple little story about a boy growing up in a small African village. I found it through its illustrations, which are phenomenal.

- How to Eat Fried Worms, Thomas Campbell – Better than I thought. There’s something so boyish about the idea of sticking to such an arbitrary, unpleasant task for the sake of winning a bet.

- Al Capone Does My Shirts, Gennifer Choldenko – The book would have been far more interesting if the last chapter had been the third chapter.

- The Arrow and the Crown, Emma C. Fox – I finally read this! Well done, Emma Fox. Buy it here.

- Hush-Hush, Remy Wilkins – Finally read this, too! Well done, Remy. Buy it here.

- *The Bark of the Bog Owl, Jonathan Rogers – A fun fantasy retelling of the David story.

- Over Sea, Under Stone, Susan Cooper – I always hear about Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising, so I assumed it was the first book in the series. No, it’s the second. The adventures start in Over Sea, Under Stone, which was enjoyable. Worth having on the shelf.

Teaching (7)

- Prince Caspian, C. S. Lewis; The Golden Fleece, Padraic Colum; Gilgamesh the Hero, Geraldine McCaughrean; The Odyssey (Lombardo); The Burial at Thebes, Seamus Heaney; Watership Down, Richard Adams – Assigned reading.

- Cuneiform, Irving Finkel and Jonathan Taylor – Very good. Irving Finkel is quite a character in his own right, as you can see from this video of him teaching a Youtuber to write in cuneiform.

Theology and the Christian Life (5)

- On Earth as it is in Heaven, Peter J. Leithart

- *The Covenant Household, Douglas Wilson

- Pastor, ed. William H. Willimon

- Christianity and Liberalism, J. Gresham Machen

- *The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment, Jeremiah Burroughs – Long, but worth it. (His name should have been Jeremiah Thorough.)

Adult Fiction (9)

- *The World’s Desire, H. Rider Haggard and Andrew Lang – The further adventures of Odysseus, in which he travels to Egypt and marries Helen. I had high hopes for a Haggard-Lang collaboration, and they didn’t disappoint in terms of concept. Odysseus arrives in Egypt just as the Israelites are leaving, and in the final battle he comes face to face with a Norseman named Wolf (a Laestrygonian according to the authors, but clearly inspired by Beowulf). It’s like the Avengers for nerds of ancient literature! Unfortunately, the story is utterly flat and boring. Oh, well.

- *Greenmantle, Mr. Standfast, The Three Hostages, and The Island of Sheep, John Buchan – Excellent. A large part of the appeal of these books, to me at least, is the heroes’ combination of nerve, experience, education, lifestyle, and sense of duty. These are men I want to be like. (Except Sandy. There’s no one like Sandy. He’s in a class of his own.)

- Strangers on a Train, Patricia Highsmith – Read on the recommendation of Josh Gibbs. Very well written and disturbing.

- The 7 1/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle – Painfully bad on a writing level, but effective on the level of what CS Lewis called “narrative lust.” I finished it in a matter of hours, probably.

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Anne Brontë – Fifteen hours of listening to the audiobook only to reach an unsatisfying conclusion. Gilbert is such a whiner.

- *The Chinese Maze Murders, Robert Van Gulik – Judge Dee should be ranked with Holmes, Poirot, Father Brown, etc. as one of literature’s great detectives. It was also interesting to compare some of the tropes of Western detective stories with the world of medieval Chinese mysteries. For one thing, while Western detectives work alone, Judge Dee is always surrounded by his associates. (You can see this same trend in Asian detective movies, too.) If I can get my hands on another Judge Dee novel, I’ll certainly read it.

Non-Fiction (22)

- Something like an Autobiography, Akira Kurosawa – If you’re looking for tips on filmmaking, this isn’t the right book. It is, as it says in the title, autobiographical, about his childhood and early career. He does make some pithy comments about movies, though. Here are a few:

- “The art of motion pictures is intimately bound up with science.”

- “The films an audience really enjoys are the ones that were enjoyable in the making. Yet pleasure in the work can’t be achieved unless you know you have put all of your strength into it and have done your best to make it come alive. A film made in this spirit reveals the hearts of the crew.”

- “Although human beings are incapable of talking about themselves with total honesty, it is much harder to avoid the truth while pretending to be other people. They often reveal much about themselves in a very straightforward way. I am certain that I did. There is nothing that says more about its creator than the work itself.”

- *Plowing in Hope, David Bruce Hegeman – Helped me clarify what exactly I’m trying to do with Good Work.

- **Picture This, Molly Bang – Fascinating. Bang develops an illustration on the page and writes about what’s working and what isn’t. The best kind of instruction.

- *Essays in Idleness, Agnes Repplier – Repplier should be on anyone’s short list of essayists to read. Classic examples of the form.

- *Anabasis, Xenophon – One of those “should have read” books. Very much a diary of the journey, which would have to be severely edited to become an exciting adventure story. Still, quite a few meaty quotes and several memorable scenes. “The sea! The sea!”

- Born a Crime, Trevor Noah – Enjoyable.

- Conscience Decides, Thomas More – Probably not the best introduction to More or the best summary of his thoughts, but hey, it was on my shelf.

- Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog, Kitty Burns Florey – A fun book about diagramming sentences. Florey writes with so much personality, I find her writing very pleasant to read. (Her non-fiction, at least. I gave up on the one novel of hers I started.)

- The Dorean Principle, Conley Owens – Essentially, the thesis of this book is that ministers shouldn’t charge for their ministry. An inarguable point, perhaps, but Owens extends “ministry” to include anything that contributes to the education or edification of Christians or to evangelism of any kind. This includes Christian publishers, musicians, parachurch organizations, conferences, etc. Owens believes ministry should always be supported voluntarily, without being subject to obligation of any kind. He bases his argument on Paul’s letters, which means he has to perform a few contortions to explain Paul’s frequent requests for financial support. To be honest, I didn’t completely follow all the ins and outs of Owens’s explanation. I need to reexamine it, though, since his thesis, if true, directly impacts much of the work I am or hope to be involved in.

- **Leisure, the Basis of Culture, Josef Pieper – Very useful.

- The Black Swan, Nassim Nicholas Taleb – Good, but Antifragile is better. It covers the same ground and a whole lot more.

- **Take Ivy, T. Hayashida et al. – A lookbook of late 1960s Ivy style.

- **The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell – If you’re looking for someone with an encyclopedic knowledge of ancient myths from around the world, look no further than Joseph Campbell. If you’re looking for someone who can interpret and explain those myths, ignore Campbell and pick up a copy of Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man.

- **The Mind of the Maker, Dorothy L. Sayers – I needed to read this. Extremely helpful in pinpointing the role artists play in the Christian community.

- The Early Church, Henry Chadwick – Helpful, but it’s going to take years of study before I can keep all these heresies straight.

- The Story of the Church, Walter Russell Bowie – Useful, especially the chapters about the early and medieval church. After the Reformation, the story meanders somewhat.

- **Defending Boyhood, Anthony Esolen – Esolen tends to say the same things over and over, but he says them so eloquently, and they’re so true, I don’t mind.

- **Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child, Anthony Esolen – See above.

- **The Headmaster, John McPhee – I wrote a little about this book in one of my newsletters.

- Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning, Douglas Wilson – What a product of its time this book is. I will be forever grateful for it, but I do think we need a new manifesto for classical education.

- Planet Middle School, Kevin Leman – Good bits here and there.

- Hold On to Your Kids, Gordon Neufeld and Gabor Maté – Very good. The main thrust of the book is that parenting naturally includes an attachment relationship in which the child is oriented to the parents. As the authors say, “It is the thesis of this book that the disorder affecting the generations of young children and adolescents now heading toward adulthood is rooted in the lost orientation of children toward the nurturing adults in their lives.” […] We use the word disorder in its most basic sense: a disruption of the natural order of things.” Much more to say about this book.

Plays (2)

- The Importance of Being Earnest, Oscar Wilde – Still one of the funniest plays ever written.

- Little Women: The Musical, Allan Knee & Mindi Dickstein

Poetry (3)

- The Desk Drawer Anthology, ed. Longworth and Roosevelt – By design, a collection of semi-forgotten treasures.

- Poems That Make Grown Men Cry, Anthony and Ben Holden – Not *this* grown man. Ok, maybe a few of them made me sniffle.

- *Poems 1914-1919, Maurice Baring – Baring wrote a great translation of Pushkin’s “The Prophet,” but his sing-songy English couplets get a bit old.

Total: 68

- The Archive is one of the three free internet services I’ve ever donated to. The others are Wikipedia and Ad-Block Plus. ↩︎