Instagram in 1909

No commentary this year, though I did send a newsletter with a few highlights.

*Asterisks mark books I read on Kindle.

Total: 41

Robin Sloan is reading The Green Knight on New Years Day. I plan to read it over the Twelve Days of Christmas. That puts me in mind of other books I try to read at specific times of the year.

I wonder what other book/season pairings there are in my life. Maybe I’ll add Dandelion Wine to read over the summer.

I’m only a few chapters into Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, but already I’m convinced that the children have some of the best parents in literature.

This past summer I called Spectrum to see if they could lower the price of our internet service. Not only did they cut it in half, they threw in a free Galaxy tablet. It’s cheap as far as tablets go, but it has had a huge effect on my reading habits this year. Since I don’t really like reading books on the computer, I never really made use of the treasure trove that is the Internet Archive.1 For some reason, reading on a tablet doesn’t bother me as much, so I’ve been able to dive into all the books I can’t afford to buy. I prefer paper books, of course, as does any sane person, but it’s hard to argue with cheap. Books I read on the tablet are marked with a **double asterisk. One *asterisk means I read it on my Kindle.

Total: 68

And my great wish is, that young people who read this record of our lives and adventures should learn from it how admirably suited is the peaceful, industrious, and pious life of a cheerful, united family, to the formation of strong, pure, and manly character.

Johann David Wyss, The Swiss Family Robinson

Reading this for my own sanctification.

I may be the only person on Earth who has a Google Alert for “edmund spenser,” so I may be the only person who knows just how rarely his name is invoked in the English-speaking world. Occasionally, a rare “Una and the Lion” coin will go to auction, and every Valentine’s Day there are multiple blogs posting snippets of “Amoretti,” but ninety percent of the time, there’s nary a peep.

Once in a while, however, Spenser’s name does survive the editor’s axe. I used to post these references on my Edmund Spenser blog, but as I rarely use that site these days, I thought this was a more appropriate venue.

First, and most randomly, here he is quoted in the bridge column of the Hastings Tribune: “So double was his pains, so double be his praise.”

The website Hogwarts Professor wrote a much-deserved tribute to the great scholar Alastair Fowler, who edited CS Lewis’s book Spenser’s Images of Life, and who also shared my hatred of “new historicism.”

Exaudi, an album of choral music by Christopher Fox, contains a song based on Prothalamion:

A Spousal Verse (2004), written for the Clerks, is a harmonically rich setting of the sixth stanza of Prothalamion (1596), by the Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser. Fragments of melody are interwoven into brief contrapuntal units. Birds, Venus herself, and Peace are implored to bless the wedding, with the last verse serving as a refrain: ‘Upon your Brydale day, which is not long: Sweete Themmes run softlie, till I end my Song.'”

A brief overview of the Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey must include a mention of Spenser, of course.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips, poet, modeled a poem after the stanza form invented by Spenser. Here’s Jesse Nathan’s description in McSweeney’s:

His first book of poems, The Ground, starts with an ancient newness, a nine-line stanza repurposed from Edmund Spenser, who had used it in Renaissance England before Shakespeare was a name anyone knew. Phillips’s oeuvre begins in this way, and you aren’t meant to have to immediately hear the Spenser; that’s part of the point, that the traditions flow under the lines like an unseen river, unseen but profoundly there, not obscuring what’s on the surface but feeding it:

In the beginning was this surface. A wall. A beginning.

Tonight it coaxed music from a Harlem cloudbank. It freestyled

A smoke from a stranger’s coat. It stole thinned gin.

It was at the edge of its beginnings but outside

Looking in. The lapse-blue façade of Harlem Hospital is weatherstill

Like a starlit lake in the midst of Lenox Avenue …It was this poem, published in 2012, that announced the emergence of a major talent. Willing to draw on all the available resources, willing to cull and reject and amplify—this, the work seemed to be saying, is an urgent poetics of inventive reinvention.

Fun!

In the Cinemaholic, Diksha Sundriyal muses on the source of the enigmatic phrase “What is lost will be found” in Netflix’s show 1899:

There are two instances where this phrase appears in some form in the real world, and their context helps us understand what it might mean for Maura and the passengers. The first is the poem, ‘The Faerie Queene’ by Edmund Spenser. One of the longest poems in English literature, it follows the stories of several knights while also talking about the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. While one can take it at its face value, the poem is known for being full of allegories, with different layers to its verses.

One of the lines in the poem’s ‘The Ways of God Unsearchable‘ part reads: “For whatsoever from one place doth fall/ Is with the tide unto an other brought/ For there is nothing lost, that may be found if sought.” The last line bears some resemblance to the phrase Maura finds on the envelope. These lines talk about the place of things and how they always surface no matter how deep they are buried. If something has disappeared from its place, then it will show up somewhere else one way or another in some form. And no matter how elusive it might be, if you look for it long enough, you will eventually find it.

Last, Rebecca Reynolds has announced an interesting project: a prose “translation” of the entire Faerie Queene. In a post at the Rabbit Room, she explains:

I’ve spent the past four years working with Renaissance scholars to create a line-by-line, text-faithful prose rendering of Spenser’s work. I’ve included many footnotes referencing Spenserian scholars while offering a version of the text that allows readers to move easily through the plot. My goal isn’t to replace Spenser’s original work—that would be impossible—but to provide a transitional work that gives modern readers the confidence to tackle the original.

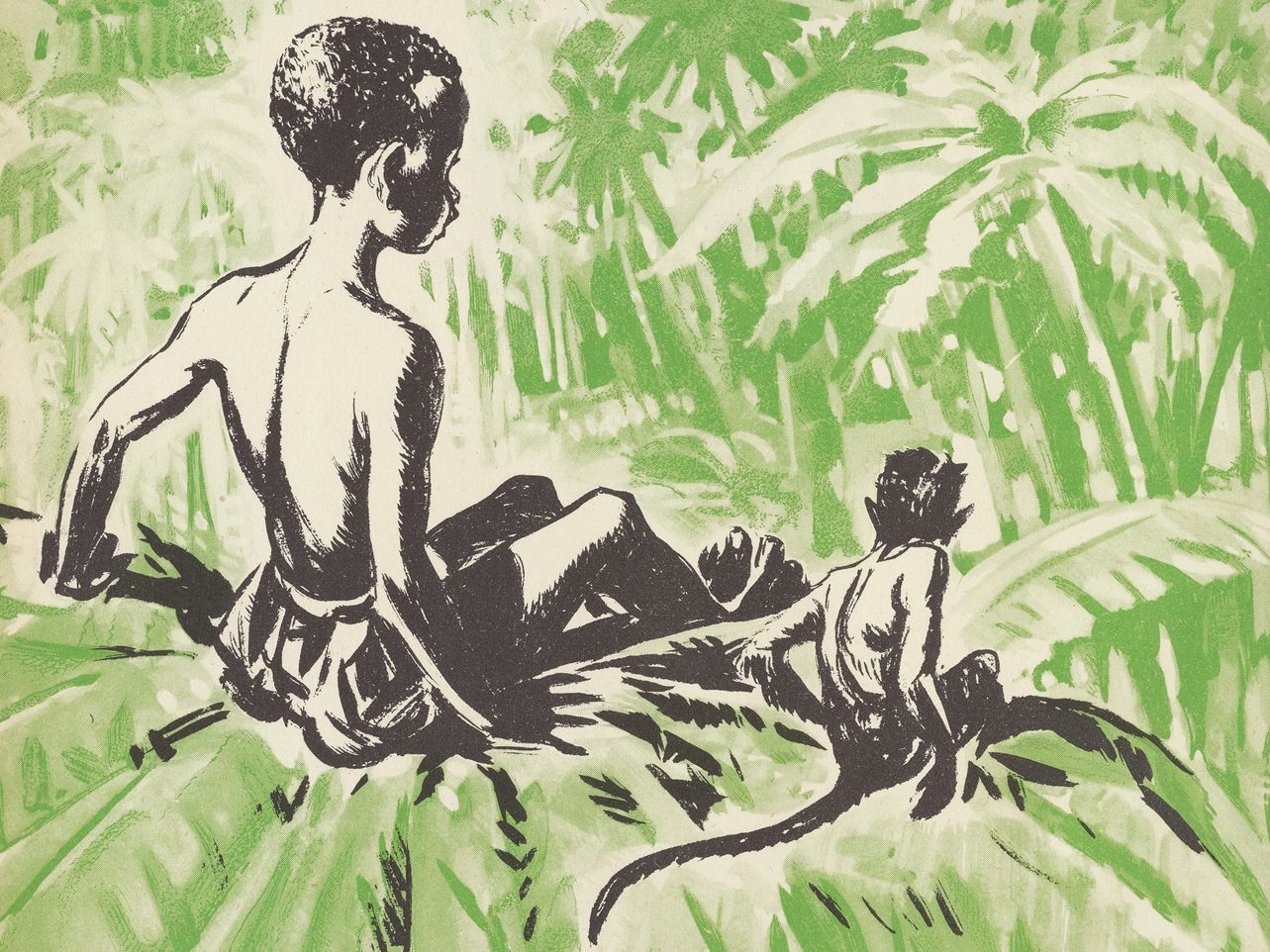

She also has a great (longish) introduction to Spenser and the Faerie Queene on her website. And be sure to check out the awesome illustrations.

Total: 86