Browsing the internet often results in serendipitous connections. Pair this quote from Steve Conner (via Sara Hendren)…

Disabled sports are the only kind there are.

… with this essay by Alan Jacobs about how art needs resistance to flourish.

Browsing the internet often results in serendipitous connections. Pair this quote from Steve Conner (via Sara Hendren)…

Disabled sports are the only kind there are.

… with this essay by Alan Jacobs about how art needs resistance to flourish.

The art is greatest which conveys to the mind of the spectator, by any means whatsoever, the greatest number of the greatest ideas; and I call an idea great in proportion as it is received by a higher faculty of the mind, and as it more fully occupies, and in occupying, exercises and exalts, the faculty by which it is received.

If this, then, be the definition of great art, that of a great artist naturally follows. He is the greatest artist who has embodied, in the sum of his works, the greatest number of the greatest ideas.

John Ruskin

Put this together with Charlotte Mason’s statement that the mind feeds on ideas (and is thereby educated) and you may conclude that great art is the best tool of educating the mind.

I’ll have to return to this later.

The school asked me to write something about the Christian values reflected in our fall play, The Importance of Being Earnest. You can read it below. But first, behold this illustration of the play’s opening scene by one of the young actors.

Here’s the blurb:

Worn out by being a constant model of respectability at his country estate, young Mr. Jack Worthing occasionally pops up to London to visit his imaginary and very badly behaved brother Earnest. In London, Jack steps into the role of Earnest, entertaining himself and his ne’er-do-well friend Algernon Moncrieff. When the fun is over, Jack retires to the country, where he once more plays the part of role model.

Most of the social satire in The Importance of Being Earnest has leaked out since it was first performed in 1895, and what remains is almost pure farce. No one in the play has his head screwed on straight, and the plot is barely believable, but that is no doubt what has contributed to its ongoing popularity. It is ridiculous, yes, but life is often ridiculous. The characters are silly, but who among us has not been silly? The key is to recognize the fact. Jack Worthing tries to keep life and fun in separate boxes and consequently finds it almost impossible to laugh at himself. His constant seriousness is, as Algernon dryly remarks, a sign of “an absolutely trivial nature.” The graver Jack is, the fussier he gets over the smallest things in life.

Oscar Wilde subtitled his play “A Trivial Comedy for Serious People.” Perhaps the most important thing about The Importance of Being Earnest is its triviality. The wise man knows that not everything can be taken seriously, least of all himself, and the play reminds us of this truth.

Too much gravity flattens a man, but a little comedy will restore him to his natural shape.

1 Apply the seat of your pants to a chair in a very quiet room.

2 Focus with undivided attention. There shouldn’t be any distractions, especially no music blasting through earphones.

3 Conceptualize, conceptualize, conceptualize. Students often say they made a design because they felt like it. They too rarely say they did it because they thought it through and wanted to use THIS concept.

4 Sketch out thumbnails with a thick black marker—a pencil or pen will make your drawings too fussy. Fussy is good when refining an idea, but you can’t refine “nothing.”

5 Ask yourself questions to help define the problem—you are your own best resource.

6 Push yourself to explore something new. There are wonderful things inside you, and if you don’t try things you’ve never done before, you will never find them. Keeping yourself off balance will help.

7 Enlarge some of your thumbnail sketches. There are times when a wonderful little fragment of a drawing is there, but you don’t know it or see it when it’s too small. Do it mechanically—on a copier or scanner. The tools are there, so use them.

8 Don’t be afraid to put stupid things down as ideas. The point is to keep moving forward—you can weed out bad ideas later.

9 Use symbols. Don’t make pictures of whatever happened—there is rarely an idea in that approach. BUT, don’t take the search for a symbol too literally by making a trademark.

10 Be your most severe critic. The only person you ought to be competing with is yourself. Push yourself in your sketch phase. Think of it as climbing a hill with a rock on your back—it seems like you are never going to get anywhere, but what you’re actually doing is investing—in the project and in yourself.

From Guide to Graphic Design, by Scott W. Santoro, Pearson Education; it came to me via Scott W. Santoro

See some of Goslin’s designs here.

A friend read the introductory paragraph of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy’s The Christian Future at Men’s Group this weekend. Here it is:

ERH goes on to say that this “speechless future,” as he calls it, is the dilemma of our age and was the theme of his life for several decades.

I found myself unexpectedly moved by this anecdote, in particular the line, “When a lover has nothing more to say”—nothing, that is, except “to Hell.” When not even love can move a man to care about beautiful speech, what hope is there for speech at all?

I’m not old enough to call this dilemma the theme of my life, but it has certainly been a preoccupation. I spend the bulk of my time making art and teaching others to make art for themselves. Almost everything I do, whether teaching literature, organizing a music colloquium, or publishing a magazine, is part of this project: to make the best art I can and teach others to make it, too.

The artist’s main challenge (apart from just doing the work) is getting other people to care. In fact, that may be the best way to measure the success of any given artwork. Does it compel people to care? The theater producer in the story gives up his dreams because he thinks that his cause is hopeless. Granted, a public that has no response other than to say “to Hell” makes a tough crowd, but I hold out hope that it can be won over. Eventually, that apathy will break under its own weight and people will begin looking for things to care about.

And once they care, they will need words to say. One day, a young Romeo spending an evening with his Juliet may realize that he does want to woo her with beautiful speech, and he will search high and low until he finds something. So this is my encouragement to artists and teachers everywhere: Keep making and loving beautiful things. One day, the world will want them again.

Underneath his project was the old-fashioned and yet novel assumption that profound creativity is always a sign of profound mental health.

From this article on Joseph Frank’s biography of Dostoevsky

The first issue of my newsletter went out this morning, including a short essay I called “Writing in War-Time.” You can read it below, and, if you so desire, you can subscribe to the real deal here.

In 1939, almost two months after England declared war on Germany, C. S. Lewis gave a lecture about the importance of studying the humanities during a World War. Why waste time with such “placid occupations” as philosophy and literature, he asked, when men are dying in battle and the threat of invasion hangs over the nation?

We’re not in the middle of a World War, thankfully. But many of the same conditions that Lewis was concerned with exist today. A lot of people around the world are in very real danger, if not from the mysterious plague known as COVID-19, then from riots and civil unrest. It’s hard to read the headlines without dread. In such an environment, we may ask the same question Lewis poses: why spend time doing anything but the most essential activities?

Of course, what activities qualify as “essential” changes depending on who you ask (shopping? protest? worship?), but the question remains the same. In extreme circumstances, how do we justify wasting time on non-essentials? In Lewis’s lecture, “non-essentials” include studying the humanities. For me, they include writing children’s fiction and mulling over poetry while staring at the wall.

In his typical fashion, Lewis reframes the whole conversation. It’s wrong to ask whether studying (or writing) is the right thing to do in the middle of a war, he says, because the question assumes that war presents an unusual danger that must be met with an unusual response. The reality is that we are always in danger of our lives. None of us can be sure that he will be alive tomorrow. A better question, then, is whether studying or writing is ever the right thing to do. Why spend time reading Aristotle when you could be protesting? Why spend time writing poems when you could be saving souls? Why not do things that matter?

Lewis answers the question from many angles, but part of his answer is this: we waste time on “non-essentials” because we can’t help it. It’s human nature to play cards on the eve of battle. When city workers tore down a Confederate memorial in Birmingham in the middle of the night last week, they stopped for a pizza break. Even SWAT teams crack jokes on duty.

In the direst circumstances, people stubbornly remain people. They keep on humming, snickering, debating, reading, reciting, and contemplating. This means that they need good songs to hum, good jokes to laugh at, good ideas to debate, good books to read, good poetry to recite, and good art to contemplate. As Lewis says, “You are not, in fact, going to read nothing, either in the Church or in the [battle] line: if you don’t read good books, you will read bad ones. If you don’t go on thinking rationally, you will think irrationally. if you reject aesthetic satisfactions, you will fall into sensual satisfactions.”

Writing in the midst of pandemics and protests is, from the vantage point of eternity, not that different from writing at any other time. The only difference is that it’s much easier to get distracted. But the importance of the work remains unchanged. The world will have stories, and those of us who are blessed with the opportunity to write them must give the world good ones.

The world is calling us to action. But what should the artist do? Should artists set aside our pens and paintbrushes and pick up swords? The answer is far simpler and far more difficult. In times like these, the artist ought to stick to his work. Are you a chef? Make delicious food. Are you a musician? Play beautiful music. Are you a filmmaker? Capture moments in time. This present moment needs good works of art no more or less than any other, which means that it needs them vitally.

[W]hen we observe, as we must allow, that art is no better at one age than at another, but only different; that it is subject to modification, but certainly not to development; may we not safely accept this stationary quality as a proof that there does exist, out of sight, unattained and unattainable, a positive norm of poetic beauty? We cannot define it, but in each generation all excellence must be the result of a relation to it. It is the moon, heavily wrapt up in clouds, and impossible exactly to locate, yet revealed by the light it throws on distant portions of the sky.

Edmund Gosse, “On Fluctuations of Taste”

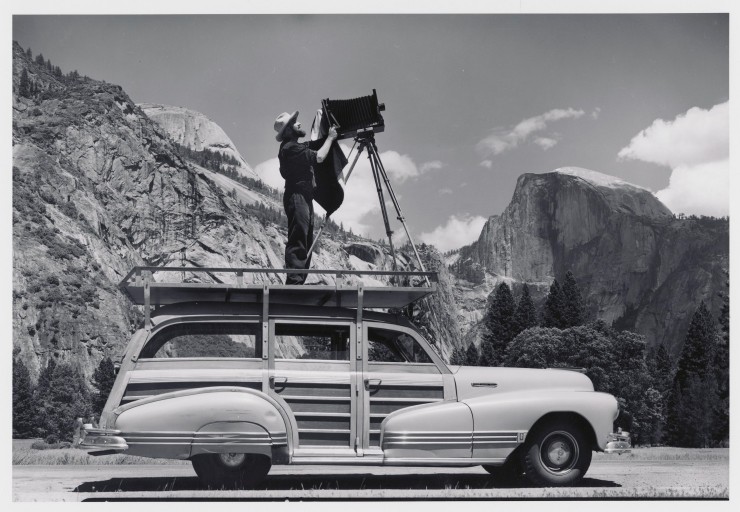

I don’t know much about Ansel Adams. I’d only recognize a few of his pictures without help. But since he was one of the best black-and-white photographers of the 20th century, I need to know something about him. Last July, I got the book Examples: The Making of Forty Photographs to learn.

The first thing that struck me was that Adams never uses the phrase “take a picture.” He always, without fail, says, “make a picture.” For him, pictures do not exist, waiting to be snatched. They must be made. He describes all the ways he framed, exposed, and washed his photos to get the desired effect.

Speaking of the desired effect, Adams writes a lot about the importance of visualizing your image ahead of time. It’s not enough, apparently, to just snap a photo and decide what you think about it later. You must pre-conceive the image so that you know what you’re going for. This is what Adams calls the “internal event,” which he explains in this short clip.

The whole key lies very specifically in seeing it in the mind’s eye, which we call visualization. The picture has to be there clearly and decisively, and if you have enough craft and, you know, working and practicing, you can then make the photograph you desire.

I think this same technique can be applied to arts other than photography. Often, when I begin a poem or an essay or a story, I meander around on the page, trying to get my thoughts in order. I would say this is the equivalent of taking a walk, looking for subjects to make photographs of. Eventually, my imagination catches on something and I have an impression (not quite a visualization) of what the final written product could be like.

I’m sure everyone has experienced some version of this. How often have you been talking with your friends when one of you says something and you think, “That would make a good movie?” In a way, you have preconceived the whole story in your head, based purely on one offhand comment. Of course, the final product is rarely like what exists in your imagination, but that’s where the craft comes in. All the artist’s work and practice is for making the most of those moments of visualization.

The principle of growth means we have to move on, but it also means that we cannot move on until we understand our heritage. To try to generate good church music out of the meager vocabulary of American popular music is like trying to generate good theology out of the ideas heard on Christian radio and television. Christian theologians need to acquire familiarity with the whole of the Christian past, in constant contact with the primary special symbols, in order to move forward into new man-made theologies. Christian musicians must know all the music of the Christian past, in constant contact with the primary special symbols, in order to produce good contemporary Christian music.

James Jordan, Through New Eyes, p. 37

If you took a gander at my media diary, you’d notice that I spend a lot of time reading theology. Why be theologically literate, you might ask, if you write fiction? What’s the point? The point is exactly what JBJ explains above: in order to produce good Christian stories, the writer must be in constant contact with the primary special symbols, which means reading, examining, and knowing the Bible.