I’m really enjoying Betty Edwards’ Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. I’ve even done some of the exercises, and as far as I can tell, they are extremely effective. I get drawing in a way I never have before. (When I was fourteen or so, a friend told me that the key to drawing was to pretend that what you saw was a flat surface. At the time, I was convinced she was cheating — that real artists were constantly aware of 3D space, but as it turns out, she was right.)

Edwards’ main point is that we use our left brain (logical and verbal) to recognize objects around us without actually seeing them. To do this quickly, we catalogue objects according to certain traits and skip over the details. That’s fine for getting through life, but when we try to reproduce what you see on a piece of paper, we fall back those traits and communicate them symbolically. For example, a stick figure is recognizable as a person, but it doesn’t really look like a person at all. It’s a symbol.

Edwards teaches her students to turn off their left brains and look at objects without mentally categorizing them. (I posted one of her exercises here.) When they get into what she calls “R-mode” (right brain), they experience a sort of altered state of consciousness. Here’s how she describes some of its characteristics:

First, there is a seeming suspension of time. You are not aware of time in the sense of marking time. Second, you pay no attention to spoken words. You may hear the sounds of speech, but you do not decode the sounds into meaningful words. If someone speaks to you, it seems as thought it would take a great effort to cross back, think again in words, and answer. Furthermore, whatever you are doing seems immensely interesting. You are attentive and concentrated and feel “at one” with the thing you are concentrating on. You feel energized but calm, active without anxiety. You feel self-confident and capable of doing the task at hand. Your thinking is not in words but in images and, particularly while drawing, you thinking is “locked on” to the object you are perceiving. On leaving R-mode state, you do not feel tired, but refreshed.

My drawing ability is mediocre, but I do recognize what she’s describing. I’ve experienced it most often when editing video. I would become completely locked in and work for hours, barely moving. I’ve heard coders describe the same thing.

What I find most fascinating about this passage, though, is how it applies to writing. When I’m fully engaged in writing, I lose track of time. When someone talks to me, I pay no attention. (I have strong memories of my dad doing the same thing when I was a child.) I am attentive, concentrated, confident, and capable. The one thing that does not match up with my experience writing is that Edwards describes this state as “not thinking in words.” In fact, that’s one of the hallmarks of R-mode. You put aside verbal processing in order to see things “as they are.”

How is it possible that writing, which is by definition a verbal activity (you’d think), can shift someone into R-mode, which is partially defined by a lack of verbal processing? I don’t know, but, a few pages later, Edwards includes this quote from Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language”:

In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is to surrender to them. When you think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualizing, you probably hunt about till you find the exact words that seem to fit it. When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning clear as one can through pictures or sensations.

I have never considered this, but I think Orwell is right. And it occurs to me that this is what poets do all the time. They consider pictures or sensations and, instead of using symbols (Edwards’ term) or the existing dialect (Orwell’s), they hunt for words that communicate as closely as possible what they are actually seeing or perceiving in the world around them.

A few years ago I decided that I was done with Goodreads. Instead, I thought, I’ll keep track of my reading on my own blog, like film director Steven Soderbergh. A big part of my reasoning was that Goodreads pressured me to finish everything I read, whereas posting a daily update of the books I dipped into let me record what I was reading while giving me the freedom to lay down a book at any time.

I kept my Media Diary faithfully for many years. About six months ago it occurred to me that, since the page was public, people could critique my reading, watching, and listening on a daily basis. Normally I wouldn’t mind. But a friend might lend me a favorite book and be offended if I don’t start it till two weeks later. A boss might happen to see that I watched a movie in the middle of the week instead of keeping up with my grading. I decided to make the page private.

Since then, I’ve basically stopped updating it. I didn’t realize how much the public gaze (or rather, the possibility of the public gaze) motivated me to post every day. The invisible audience held me accountable. So, I’ve made the page public again, until I think of a better solution.

Brian Suavé Sauvé justifies his decision to speak at the 21 Convention:

The minute I heard that pastors are speaking at this event, I knew that Acts 17 would be used to justify their decision. Paul welcomed the chance to present the Gospel to Gentiles on their own turf. Shouldn’t we?

The problem with the argument is that Paul is manifestly an outsider on Mars Hill, speaking to the insiders. He emphasizes the fact (Acts 17:23). He was not one of an array of approved speakers, preaching to an assembled crowd. The philosophers were the crowd. If Pastor Suavé Sauvé really wanted to imitate Paul, he would go to a red-pill convention on the condition that he get a private session with the speakers only. Perhaps he has done this. Perhaps not.

One more thing: Christians love jumping onto runaway trains in order to “turn things around.” It never works. Didn’t we learn something when we tried this with the public schools? Let the dead bury the dead.

UPDATE: I still don’t know about Pastor Suavé Sauvé, but another pastor who will be speaking at the conference, Michael Foster, posted this, in which he says he agreed to speak at the conference on the condition he be allowed to say whatever he wants. That is similar to what I posted above. So, good for him.

Most scholarship is also not going to live forever. Is it therefore not worth doing? I wouldn’t say so. It’s worth it to maintain gardens and repair buildings and restore artworks. No one’s work lives forever on its own. It stays alive because someone keeps it so. Here again, greatness requires humility: other people’s. The task of thinking is worthwhile even if your thoughts prove to be of limited usefulness. The tasks of reading, of appreciation, of interpretation, are worthwhile, even if next year there is a new essay that supersedes yours, or a new book. If we have chosen to live our lives this way, it is because something about it strikes us as the best way we can spend our time.

B. D. McClay

Via Ayjay, in a post, as always, worth reading: https://blog.ayjay.org/dna/

Someone on Twitter (maybe Joss Whedon – remember him?) once wrote, “I love it when my friends go internet-silent for a while, then suddenly reappear with some new project just completed.” Well, I have no major accomplishments to reveal (yet…), but here are a couple of news items from the world of Broken Bow.

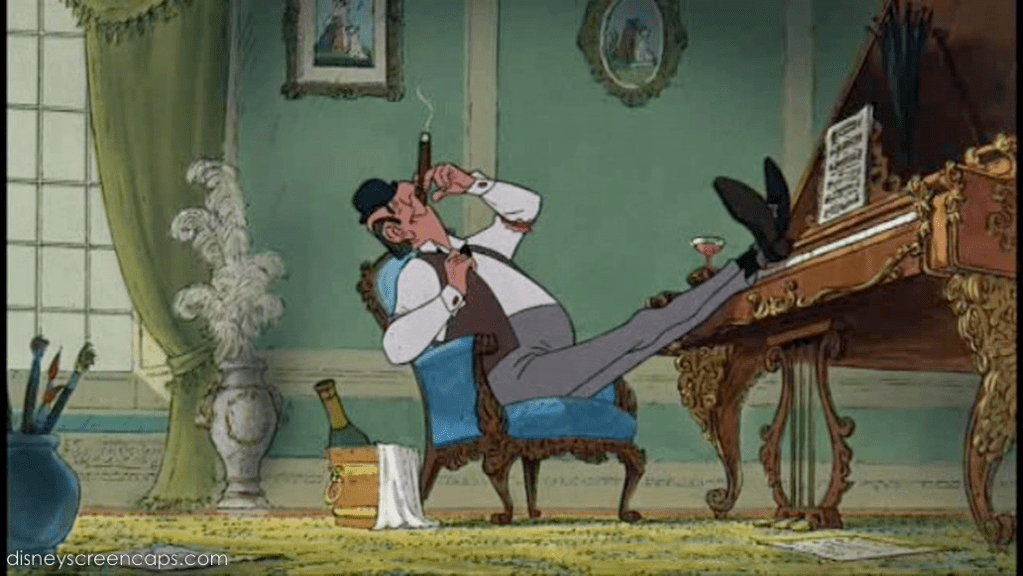

If you want to know why I boycott Disney’s live-action remakes (and why you should, too), watch this video on 2017’s Beauty and the Beast. (Thanks, Alastair, for sending it to me, even though it took me roughly three years to watch it.)

If Disney ever gets around to remaking The Aristocats as a misunderstood-villain version focusing on Edgar, I’ll fork over the dough. Otherwise, the boycott stands.

One day, on impulse, I asked the students to copy a Picasso drawing upside down. That small experiment, more than anything else I had tried, showed that something very different is going on during the act of drawing. To my surprise, and to the students’ surprise, the finished drawings were so extremely well done that I asked the class, “How come you can draw upside down when you can’t draw right-side up?” The students responded, “Upside down, we didn’t know what we were drawing.” This was the greatest puzzlement of all and left me simply baffled.

Betty Edwards, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

This is one of the funniest academic books I’ve read.

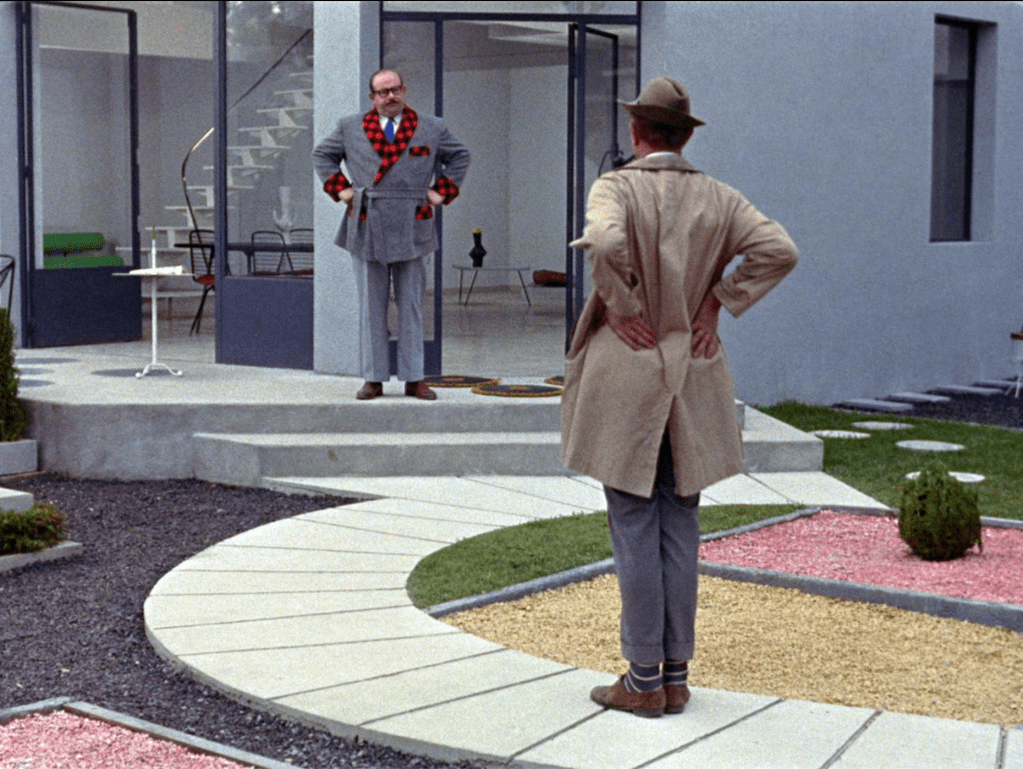

The writer Tom Wolfe used to tell me that he liked to dress different because he liked watching people watch him.

Alan Flusser